BIOGRAPHY:

Henry VIII, King of England, ruled the country from 1509 to 1547. The second member of the Tudor dynasty to the throne, from his father, Henry VII (reigned: 1485-1509), inherited a kingdom that enjoyed unity and a rich coffers. Known for marrying six times in the hope of finding a male heir, the king was charismatic and commanding. In order to obtain a divorce from his first wife, Henry came into conflict with the Pope and began the Reformation in the English Church. As a result, a break with Rome occurred, and the English monarch became the head of the church in England. With his enormous influence, Henry strengthened the state apparatus, further subjugated Wales, provoked the dissolution of the monasteries, laid the foundations of the Royal Navy and built magnificent palaces such as St. James’s Palace in London. When Henry died in 1547, he was succeeded by his young son Edward VI (reigned 1547-1553), to whom he left a ruined treasury and a kingdom torn by religious strife.

Early years:

Henry VII faced a number of challenges to his power and saw his main task as filling the state treasury, strengthening royal power and weakening the position of the nobility. The king’s eldest son was Arthur (born in 1486). In 1501 he married the Spanish infanta Catherine of Aragon, daughter of King Ferdinand II. Unfortunately, Arthur died the following year, at the age of 15. The king’s next eldest son was Henry, born on June 28, 1491 at Greenwich Palace (Placentia Palace). He became heir to the throne and in 1503 received the title Prince of Wales. Henry VII hoped to maintain friendly relations with Spain and therefore Prince Henry, after receiving special permission from the Pope, was betrothed to Catherine of Aragon. When Henry VII fell ill and died on April 21, 1509, Prince Henry became king. As planned, he married Catherine on 11 June and was crowned Henry VIII at Westminster Abbey on 24 June 1509.

Unlike later and more famous depictions of Henry VIII, in his youth the king had an athletic figure, standing at 1.90 cm (6 ft 3 in) tall, with red hair and a beard making him quite noticeable and attractive. It was not without reason that he won at the medieval tournaments that his father liked to organize. The prince was an excellent archer, horseman and tennis player. During his rest, he composed poetry, music and honed his knowledge of theology. Overall, Henry was an educated and charismatic man who charmed everyone he met. Historian John Miller describes Henry’s strong but mercurial character:

[Henry had] a strong will, was shrewd, prone to displays of incredible generosity and enthusiasm, but also to outbursts of anger. As a young man, Henry intended to enjoy the role of king and outshine all his contemporaries. As his best years passed, he became suspicious, capricious, treacherous and sometimes even cruel. (96)

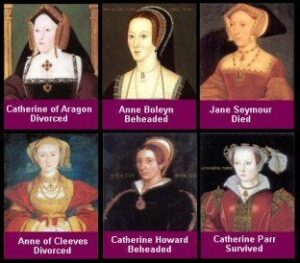

Six wives of Henry VIII:

Henry, constantly awaiting a male heir, was married six times. His wives and their children:

Catherine of Aragon (w. June 1509) – Mary (b. February 1516)

Anne Boleyn (born January 1533) – Elizabeth (born September 1533)

Jane Seymour (married May 1536) – Edward (b. October 1537)

Anna of Cleves (married in January 1540)

Catherine Howard (married July 1540)

Catherine Parr (married July 1543)

The king’s first marriage to Catherine of Aragon gave him six children, but all but one of them died in infancy. The only survivor was a daughter, Mary, born on 18 February 1516. Henry had an illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond (b. 1519) by his mistress, Elizabeth Blount. But this was not enough for the monarch, who longed to have a legitimate heir. The king began searching for a new wife and discovered the ideal candidate in Anne Boleyn, the younger sister of one of his former lovers. Anna insisted on getting married before she could think about family life. Henry’s challenge to free himself from Catherine of Aragon is now known as the King’s Great Problem.

It seemed that the solution might be to appeal to the Pope with the assumption that the lack of male offspring in marriage with Catherine was God’s punishment for marrying his own brother’s widow, an argument based on a verse from the Old Testament (“The Prohibition of Leviticus,” Leviticus 20:21 ). Due to this, the king wanted the Pope to annul his marriage to Catherine. Unfortunately for Henry, Pope Clement VII (pontificate: 1523-1534) wanted to maintain good relations with the most powerful politician of the time, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (reigned 1519 to 1556), who, very importantly, , was Catherine’s nephew. In addition, it is very doubtful that Catherine and Arthur, being very young at the time, ever shared a bed, so it would be impossible to apply the “Prohibition of Leviticus.” However, the Pope sent Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio to England to study the case and hold a special court session in June 1529. Here, both Catherine, determined to retain her status as queen, and Henry, intent on obtaining permission to marry again, presented their views on the case.

Despite Campeggio’s efforts, the problem was not solved. Henry’s next move was to separate Catherine from her daughter and move the queen from one dilapidated castle to another throughout England. During this time, Henry and Anne Boleyn lived together (although they did not share a bed). Around December 1532, Anna, probably realizing that the child would help her get rid of Catherine, agreed to have an intimate relationship with the king and became pregnant. At great cost to the Church, Henry was finally able to have his marriage annulled the following year (see below). Catherine died of cancer in January 1536. With Anne Boleyn, often referred to as “Anne of a Thousand Days” in honor of her short time on the throne and in the heart of the king, Henry received a second daughter, Elizabeth, born on September 7, 1533. However, when It turned out that the queen was having an affair on the side, and the king’s attention had already been attracted by his future next wife, Henry ordered Anna’s execution. The accusations, which included every possible sin from incest to witchcraft, were false. The king was tired of his stormy relationship with Anna, and moreover, she was unable to give Elizabeth a healthy brother and the king a son. Anne was found guilty and executed in the Tower of London in May 1536. A few weeks later, Henry married for the third time, to Jane Seymour, a lady of the court, who finally bore him a son, Edward, on October 12, 1537. The arrival of the long-awaited heir to the throne was accompanied by gunfire. with volleys, ringing of bells and banquets throughout England. Unfortunately, Jane died soon after this and Henry sincerely mourned her death; It is important to note that it was next to her that he wanted to be buried.

Anna of Cleves (daughter of the Duke of one of the German principalities) was the fourth wife of the monarch, but disappointed him. Henry was misled by an overly embellished portrait of the bride, painted by Hans Holbein the Younger, which he saw before the wedding. Nevertheless, he married Anna, although he called her a “Flemish mare.” A few months later, the king changed his mind, and the newlyweds divorced by mutual agreement on July 9, 1540. Anne was satisfied that she had saved her life, and Henry provided her with maintenance, which allowed Anne to lead a comfortable life until her death in 1557.

Henry’s fifth wife was Catherine Howard, a lady of the court and practically a teenager at the time, who attracted the king’s attention. Catherine suffered the same fate as Anne Boleyn when she was accused of having an illicit affair with a certain courtier, Thomas Culpeper. The evidence for the prosecution was a love letter presented to Parliament at her hearing. Catherine was executed at the Tower of London in February 1542.

The sixth and last wife was old Catherine Parr, by this time already twice a widow. Catherine, at that time she was over thirty, was a more mature woman than her recent predecessors, perhaps that is why this marriage was successful and family life developed happily. Catherine outlived Henry, but died from complications during childbirth in September 1548.

Government:

Unlike his predecessors in the Middle Ages, who relied on oaths of vassalage, Henry structured his court so that even low-born aristocrats could count on advancement if they could attract the king’s favor. The monarch carefully selected a number of distinguished confidants to lead the country, and among them was Thomas Wolsey (1473-1530). Wolsey was the son of a butcher, but he would eventually rise to the rank of cardinal and archbishop of York. One of his successors as the king’s first minister was an equally ambitious man – Thomas Cromwell (1485-1450), the son of a blacksmith. Both Wolsey and Cromwell ultimately displeased the king – the former was unable to resolve the “king’s great problem”, and the latter was responsible for the unfortunate episode with Anne of Cleves. Both were accused of treason and convicted. From 1540, their role was taken over by the Privy Council, which regained its former importance. The government was now a cabinet of ministers instead of one first minister, who had great influence over the king. Henry VIII also successfully interacted with Parliament, this body of power gained strength during the reign of the king.

In 1536 Wales was further incorporated into the English polity and divided into 13 counties in 1543. English became the official language and Welsh was banned from the administrative apparatus. Coping with Ireland proved more difficult, but the king’s desire to create a centralized state was reinforced by the fact that he took the title of King of Ireland in 1541, while previous kings of England called themselves only Lords of Ireland. Finally, the remote northern regions of England had been under the strict control of the Council of the North since 1536.

Church of England:

Henry was an expert in theology and had no intention of leaving such an important organization as the church to its own devices. The king wrote a treatise directed against Lutheranism, for which the Pope awarded him the honor of calling himself “Defender of the Faith” (fidei defensor – the abbreviation F.D. remains on coins in the United Kingdom to this day). The relationship, however, soured when Henry demanded an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon and accused the Pope and Cardinal Wolsey of obstructing the issue. Wolsey was accused of treason and died before his trial in 1530. When Thomas Cromwell took up this case, Henry was ready to make a final decision: England would have its own church, independent of Rome. Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, annulled Henry’s first marriage in May 1533 (although Henry and Anne Boleyn had already married in secret a few months earlier). The annulment and the fact that Parliament approved the Act of Succession (30 April 1533) meant that Catherine’s daughter, Mary, was declared illegitimate. Anne Boleyn was crowned in June and her daughter Elizabeth, born in September 1533, officially became the legal heir to her father’s throne. Henry was excommunicated by the Pope for his actions, but by this time the whole situation had gone far beyond purely royal interests.

In order to replace the Pope, who stood at the head of the Church in England, Henry decided to declare himself the head of the Church of England. To achieve this, the Act of Supremacy was issued in November 1534, which meant that over Henry and all subsequent English monarchs there was only one supreme power – the power of God. The next act of this grandiose drama was the law presented to Parliament in 1536 on the destruction of monastic life in the kingdom – the dissolution of the monasteries. The law was approved and the lands of the monasteries were redistributed between the crown and Henry’s supporters. The abbots of the monasteries of Glastonbury, Colchester, Reading and Woburn were executed and the last monastery to close was that of Waltham, Essex, in March 1540.

Many of the king’s subjects were happy about the reform of the church in England, thereby continuing the work of the Reformation, which captured the whole of Europe. Many considered the Church too rich, and the priests were accused of disgracing their positions. Of course, not everyone agreed with Henry’s break with the Pope. Thomas More (1478 – 1535), Henry’s former chancellor, was against the king’s divorce from Catherine and his claims to supreme power in the church. More was executed for his beliefs in July 1535.

The most notable manifestation of dissent took place in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, when Catholics gathered to protest in the form of the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536. The King, however, did not tolerate any opposition and 178 participants in the events, among them the leader movement Robert Ask, were executed in June 1537. Another step towards independence was permission given in 1539 by the king to translate the Bible into English. It is important to note, however, that Henry did not set out to reform the fundamental doctrines of the Church. From the Act of Six Articles, issued in 1539, it clearly follows that he remained committed to the basic religious practices of Catholicism – mass, confession, celibacy of the clergy.

Foreign policy and spending:

A medieval monarch to the core, Henry VIII seemed to disdain the surrounding reality, Europe, which had already emerged from the Middle Ages, and launched several military campaigns, just as his predecessors had done before him. Although his sister, Margaret (b. 1489), married the Scottish king James IV (reigned 1488–1513), Henry sent an army north and won a resounding victory at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. where James IV died. Another invading army attacked Edinburgh in 1544, but was defeated at Encrum Moor in 1545. Scotland became an ongoing problem that Henry’s successors subsequently tried to solve. Henry, again, like many of his predecessors, could not resist the temptation to try to conquer France. However, of his several invasions, only one resulted in a minor naval victory at the Battle of the Spurs (Battle of Guinnegat) on 16 August 1513. Henry changed tactics and married his sister Mary (b. 1496) to Louis XII, King of France ( 1498-1515) in 1514. In 1518, Henry decided to consolidate the status quo in Europe and signed a mutual defense treaty with France, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. In order to pay for these on-and-off wars in France and Scotland, Henry had to sell lands confiscated from the church to aristocrats willing to pay a decent price. The high costs and poverty of the English treasury, compared with the wealth of France, forced Henry to abandon a number of military campaigns in the 1540s. The best decision taken was to conclude a peace treaty in 1546, which resulted in control of Boulogne for eight years.

A more successful enterprise on French soil was the Camp of the Cloth of Gold (Field of the Cloth of Gold), a stunning demonstration of luxury and wealth, staged near Calais in June 1520. The event program included knightly tournaments, hunting, feasts, which took place in specially constructed richly embroidered tents made of expensive fabric (hence the name). The event demonstrated the friendship of England and France, the friendship of two kings: Henry and Francis I (reigned 1515-1547).

Another success of Henry, very important for the further history of England, was the creation of the Royal Navy. The fleet included the large warships Mary Rose and Henry By God’s Will (also known as “Big Harry”). The former was a magnificent flagship, but sank in the Solent in 1545 with the loss of 500 people. The wreck was raised in 1982. Wanting to make a lasting impression in all his affairs, Henry built the magnificent palaces of Whitehall and St. James’s in London, and also significantly rebuilt Hampton Court. The grandest of all was the Unseen Palace in Surrey, the king’s personal entertainment estate built to celebrate the 30th anniversary of his reign. The name of the palace emphasized that such luxury had never existed anywhere before. In fact, the building was exceptional, here the king could enjoy his favorite activities, including falconry. The unprecedented palace was never completed and after the death of the king passed from one owner to another until it was finally destroyed in the 17th century.

All 60 of Henry VIII’s houses were richly decorated with tapestries, works of art, and gold and silverware. However, towards the end of his reign, the king squandered his funds on military campaigns and entertainment, so that practically nothing remained of the funds accumulated by his father. Henry, cruel and vindictive, had almost no friends, and the kingdom was divided on the basis of religious hostility. Henry, whose early reign inspired so much hope, left behind him little of value other than a profusion of portraits reflecting the vanity of a man blinded by the illusion of grandeur.

Death and successors:

In the last years of his life, Henry VIII’s health deteriorated rapidly. The King of England suffered from leg ulcers and obesity. Its weight was so great that it had to be transported on a special structure with wheels. The king died on January 28, 1547 at Whitehall in London, aged 55. Henry was buried in St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, next to his third wife Jane Seymour. Henry was succeeded by his son, Edward VI, who was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 20 February 1547. Edward was only nine at the time and subsequently died of tuberculosis in 1553, aged 15. He was succeeded on the throne by his half-sister Mary I, who also reigned briefly and died in 1558. After this, the second daughter of Henry VIII, Elizabeth I (reigned 1558 – 1603), became queen, and with this reign the Golden Age of England began.