BIOGRAPHY:

The Holy Emperor Constantine I the Great remained in history as a great defender and zealot of the Christian faith. The Church awarded him the title of Equal-to-the-Apostles, despite the fact that the ruler’s biography had many unpleasant episodes, including the execution of his own wife and son.

Childhood and youth:

The future Roman emperor was born in Naisa, a city in Upper Moesia (today it belongs to Serbia and is called Nis). His full name was Flavius Valerius Aurelius Constantine; he was the son of Caesar (junior emperor) Constantius Chlorus, but not from his official wife Theodora, but from his concubine (concubine) Helen.

The exact year of birth has not been established; according to a number of sources, it can be assumed that it was the 272nd. Later, Constantius had to separate from Helen and, for political reasons, marry Maximilian’s stepdaughter. As a result of his next marriage, Konstantin had three brothers and three sisters.

Wars:

Young Constantine enlisted in the army in Nicomedia and took part in campaigns in Egypt and Persia. In 305, his father, who had become emperor in the western part of the country, summoned his son to help him in the British battle against the Picts. When Constantius died a year later, the troops immediately recognized Constantine as the legal heir, but officially he received only the status of Caesar.

At that moment, 6 people claimed the title of the main leader of the empire, which caused political strife. In 307, Constantine secured the throne by marrying Fausta, the daughter of his main rival Maximilian. He later attempted to illegally seize power, after which he was forced to commit suicide. Constantine also removed the remaining rivals by arranging profitable marriages and other political intrigues.

Politics and religion:

In 312, Constantine advanced to battle in a Roman suburb near the Milvian Bridge, where, according to legend, he saw a sign of his destiny – a fiery cross in the sky. According to another version, the emperor had a prophetic dream in which he was ordered to place a monogram of the first letters of the name of Christ on the shields of his soldiers. One way or another, the battle was won, and after the victory, the designated symbols appeared on the imperial banner – the labarum.

After this, Constantine, in the Edict of Milan, granted freedom of religion to the citizens of the empire. Christianity acquired the status of a “permissible religion”; by the order of the emperor, persecution of followers of Christ and attempts to take away property from the church were prohibited.

Later, Constantine had a conflict with his relative Licinius, who helped him in public administration. He, who for the time being obediently played the role of governor in the eastern part of the country, rebelled and declared war, simultaneously resuming the persecution of Christians on his territory. Constantine defeated Licinius in 2 battles and removed him from power, becoming the sole ruler of the Roman Empire.

It was his reign that gave rise to the spread of Christianity in Europe. Constantine’s mother Elena endeared him to him, and his father also patronized Christians, considering them respectable and honest citizens. The emperor liked even more the firmness and loyalty of the representatives of this religion to their teachings, especially considering the horrors with which their persecution sometimes turned out.

The ruler’s arrival to Christianity took place gradually – for example, he celebrated his first victory over his rivals in the temple of Apollo, making abundant sacrifices to God. Sympathy for another faith began to appear in Constantine after military victories. The aristocratic elite did not approve of the ruler’s views. In Rome, the power of pagan beliefs was especially strong, which ultimately influenced the emperor’s decision to deprive the city of capital status.

Constantine received baptism only at the end of his life, but he strongly encouraged representatives of the Christian church and consistently pursued a policy of protecting them. He actively intervened in issues of church government: in 325, at the First Ecumenical Council, he took part in resolving disagreements over the teachings of the Arians and subsequently attended its meetings several times. After another 5 years, the ruler moved the capital to Constantinople, which later became the spiritual and political center of the Byzantine Empire.

Personal life:

Only fragmentary information has been preserved about the ruler’s personal life. It is mentioned that the matron Minervina gave birth to his eldest son and heir to the throne, Clispus, but whether she had the status of an official wife or a concubine is not known for sure. She was not the first woman in his life, but there was no mention of her predecessors in the documents.

In 307, Constantine married Flavia Maxima Faustus, daughter of Maximilian. It was a dynastic marriage with the aim of strengthening political influence, but the emperor greatly respected his educated and energetic wife, who bore him six children (three sons and three daughters). Fausta was involved in the overthrow of her father and became the culprit of the tragedy that overshadowed the last years of the life of the famous Roman ruler.

In 326, Constantine ordered the execution of his own son Flavius Julius Crispus along with his nephew Licinian. The reasons for this decision are various; the most popular version is that Crispus was executed due to the slander of Fausta, who accused him of attempted rape. The accusation was false – she used this method to get rid of the main heir in order to clear the way for her sons to the throne.

The treacherous Fausta paid in full for her crime – a month later Constantine revealed the deception and ordered her to be locked in a bathhouse, where she suffocated (according to another version, her angry husband pushed her into hot water). The execution of his wife was followed by reprisals against the emperor’s friends, whom he considered involved in the case. He later put Fausta’s name under the curse of memory (forbidding any posthumous mention of her), and his heirs left this order in force.

According to legend, it was moral torment after the death of his loved ones that led Constantine to the Christian faith. However, a number of modern historians reject this version: there are facts indicating that by the time of the death of his wife and son, he had already been professing this faith for 10 years and his baptism was a long-thought-out decision.

The role of Emperor Constantine in the convocation and organization of the First Ecumenical Council:

The spread of heresies, which began in the early days of the Church, during the era of persecution, did not stop even after Christianity breathed freely. The heresy of Arius, an Alexandrian presbyter, acquired particular significance during the reign of Emperor Constantine.

At one time, this shepherd, motivated by ambition, entered into a dispute with Bishop Alexander and slandered him, accusing him of perverting the teaching about God. Very quickly, from slanderous criticism, a false doctrine was formed, according to which the consubstantiality of the Son with the Father was denied, and the Son was recognized not as a generation, but as a creation of God the Father.

Despite the apparent obviousness of the absurdity of the new teaching, it soon spread beyond Alexandria. Supporters began to gather around Arius, including virgins, deacons, priests, and bishops. The situation became more tense the more the preachers of this blasphemy multiplied. Among other things, the sharp increase in the number of heretics was facilitated by the lack of clearly developed theological terminology.

To the Local Council convened in Alexandria, which condemned Arius and exposed his false teaching, the heretics responded with a Council in Bithynia, which recognized Arius as innocently convicted.

Emperor Constantine, having received news of the growing disputes, was greatly saddened and considered it his duty to intervene in the situation personally. Unrest in the Church worried him both as a sovereign and as a sympathizer of Christianity. And he sent Hosea of Corduba to Alexandria with a letter of exhortation. However, this measure did not bring the heretics to their senses. In addition to these internal difficulties, others were added.

And then, driven by the desire to resolve the growing problems in the Church, the king, on the advice of the bishops, decided to convene a Council. The heads of all Churches were ordered to come to Nicaea.

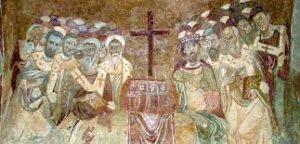

Thus, in 325 the First Ecumenical Council took place. He united 318 bishops. After lengthy discussions, the Council confirmed the consubstantiality of the Father and the Son, formulated the Creed (which was supplemented and finalized at the Second Ecumenical Council) and condemned the doctrine of the creation of the Son by the Father.

Arius and the bishops who refused to subscribe to the conciliar definition were sent into exile.

The activities of Emperor Constantine after the Ecumenical Council:

Despite the decisions made by the fathers of the Council, the Arian ferment did not stop. Moreover, on the basis of this teaching, various directions of heresy were determined: radical and more moderate.

In 328, Alexander of Alexandria died and Athanasius the Great took the see of Alexandria . A faithful supporter of the purity of Orthodox ideas, a man of holy life, he waged an irreconcilable struggle with Arianism. Unable to stop Athanasius with dogmatic arguments, the champions of heretics used the old proven method and began to intrigue. They began to accuse the saint: allegedly, having burst into the temple, he knocked over the cup with the Holy Blood; then he allegedly sent a box of gold to a certain usurper Philumen.

In 332, Athanasius was summoned to the emperor. However, after a conversation with the saint, Constantine spoke kindly about him.

In 335, associated with the approach of the thirtieth anniversary of Constantine’s reign and the completion of the construction of the basilica over the Holy Sepulcher, the emperor summoned bishops to Jerusalem. However, before this they had to gather in Tyre for the Council. The Tsar wanted peace to finally be established at this Council. There, according to the inspiration of Constantine, Athanasius the Great was also to appear .

At this Council, a new accusation was brought against him, somewhat strange, as if he, having killed Bishop Arseny, left his hand for sorcery. Having left Tire, Athanasius reached Constantinople, achieved a meeting with Constantine and pointed out to him the insignificance of the charges being raised.

Unfortunately, during the reign of Constantine, Arianism was never exterminated.

At the end of his earthly life, the emperor accepted Holy Baptism. In 337, on the day of Pentecost, he quietly departed to the Lord.

From him we have received: the Edict of Milan on the freedom of the Christian faith, the Epistle to Bishop Alexander and the presbyter Arius, the Epistle to the Alexandrian Church against Arius, the Speech of Emperor Constantine to the Holy Council, the second Speech of Emperor Constantine to the Holy Council, an excerpt from an admonishing speech to the bishops before their departure from Nicaea after the council, Epistle from Nicaea to the bishops who were not present at the council, Epistle to the Nicodemuses against Eusebius and Theognis, etc.

Death:

In 336, the emperor felt unwell and, fearing a sudden death, began to put his affairs in order. He successfully completed the war against the Gothic and Sarmatian tribes and ordered that after his death the empire be divided between his three sons: Constantius received Asia and Egypt, Constans – Africa, Italy and Pannonia, and Constantine II – Britain, Spain and Gaul.

Early next year, the ruler went for treatment. He started with the baths in Nicomedia, later went to the hot springs of Drepan and visited the baths of Elenopolis, but he did not feel better. Konstantin spent the last months of his life in a villa in Ankiron. Feeling the approach of death, he ordered himself to be transported to Nicomedia and there, on his deathbed, he was baptized.

The emperor’s dream was to be baptized in the waters of the Jordan, but he could no longer get there. It is unknown what exactly illness caused his death, but there are references to the fact that in his old age he leaned towards the Arian movement of Christianity, and the baptismal ceremony was performed by Father Sylvester.

Many scientific, religious and artistic works have been written about the life of the emperor and his contribution to the spread of faith, and several films have been made. The most famous is the Italian-Yugoslav film directed by Lionello De Felice “Constantine the Great”, released in 1961.