BIOGRAPHY:

Hughes was born on 25 September 1862 at 7 Moreton Place, Pimlico, London, the son of William Hughes and the former Jane Morris. His parents were Welsh. His father, who worked as a carpenter and joiner at the Palace of Westminster, was from North Wales and spoke fluent Welsh. His mother, a domestic servant, was from the small village of Llansantffreid-y-Méchan (near the English border) and spoke only English. Hughes was an only child; at the time of their wedding in June 1861, his parents were 37 years old.

Hughes’s mother died in May 1869, when he was six years old. He sent him forward to be raised with relatives in Wales. During term time he lived with his father’s sister Hughes, who ran a boarding house in Llandudno called Bryn Rose. He earned pocket money by doing housework for his aunt’s boarders and singing in the local church choir. Hughes began his formal education in Llandudno, attending two small schools with one teacher. He spent the holidays with his family in Llansantffryd. There he divided his time between Vinllan, the farm of his widowed aunt (Margaret Mason), and Place Bedou, the neighboring farm of his grandparents (Peter and Jane Morris).

Hughes considered himself one of his own. his early years in Wales as the happiest time of his life. He was immensely proud of his Welsh identity and he later became active in the Welsh-Australian community, often speaking at St David’s Day celebrations. Hughes called Welsh “the language of the heavens”, but his own understanding of the language was patchy. Like his contemporaries, he received no formal education in Welsh and has great difficulty with spelling. However, he received and responded to correspondence from Welsh speakers throughout his political career, famously trading insults in Welsh with David Lloyd George.

London:

After completing his initial apprenticeship, Hughes remained at St Stephen’s School as an assistant teacher. However, he was not interested in teaching as a profession, and also declined Matthew Arnold’s offer to secure him a clerkship at Coutts. His relative financial security for the first time pursued his own interests, including boating on the Thames and travel (such as a two-day trip to Paris). He also joined the Royal Fusiliers Volunteer Battalion, which consisted mainly of artisans and office workers. Hughes later recalled London as “a place of romance, mystery and suggestion.”

Early years in Australia:

Queensland At the age of eleven, Hughes was enrolled at St Stephen’s School, Westminster, one of many church schools founded by the philanthropist Lady Burdett-Coutts. He won prizes in geometry and French, receiving the latter from Lord Harrowby. After graduating from elementary school, he was a student-teacher student for five years, instructing younger students for five hours a day in exchange for personal lessons from the principal and a small stipend. At St. Stephen’s Church, Hughes met the poet Matthew Arnold, who was an examiner and superintendent for the local school district. Arnold, coincidentally on holiday in Llandudno, took a liking to Hughes and gave him a copy of the Complete Works of Shakespeare; Hughes credited Arnold with a lifelong love of literature.

At the age of 22, he found his prospects in London dim, Hughes decided to emigrate to Australia. Taking advantage of the alternative passage offered by the Colony of Queensland, he arrived in Brisbane on 8 December 1884 after a journey of two months. Upon arrival, he gave his year of birth as 1864, a deception that was not discovered until after his death. Hughes tried to find a job with the Department of Education, but was either not offered a position or the working conditions were unsuitable. He spent the next two years as an itinerant laborer, doing various odd jobs. In his memoirs, Hughes claimed to have worked variously as a fruit picker, counting, navy, blacksmith’s striker, station clerk, drover, and saddler’s mate, and to walk (mostly on foot) north to Rockhampton, west to Adawale, and south as Orange, New South Wales. He also claimed to have served briefly in both the Queensland Defense Force and the Queensland Maritime Defense Force. Hughes’s stories are by their nature unverifiable, and his biographers have questioned their veracity—Fitzharding states that they were embellished at best and “a world of pure fantasy” at worst.

N.S.W:

Hughes moved to Sydney around mid-1886, where he worked as a deckhand and galley cook on board the SS Maranoa. He found odd jobs as a cook, but one day he allegedly had to resort to living in a cave on the Domain for several days. Hughes eventually found regular work in a forge, making hinges for Colonial furnaces. About the same time he entered into a common-law marriage with Elizabeth Cutts, the daughter of his landlady; they had six children. In 1890 Hughes moved to Balmain. The following year, with financial support from his wife, he was able to open a small store selling consumer goods. The income from the store was not enough to live on, so he also worked part-time as a mechanic and umbrella worker, and his wife as a laundress. One of Hughes’ Balmain acquaintances was William Wilkes, another future Member of Parliament, and one of his store’s clients was Frederick Jordan, the future Chief Justice of New South Wales.

Beginning of a political career:

At Balmain, Hughes became a georgist, a street speaker, president of the Balmain Single Tax League and joined the Australian Socialist League. He was an organizer of the Australian Workers’ Union and may have already joined the newly formed Labor Party. In 1894, Hughes spent eight months in central New South Wales organizing the Amalgamated Shearing Union of Australia and won a seat in the Legislative Assembly at Sydney Lang by 105 votes.

While in Parliament, he became secretary of the Wharf Workers’ Union. In 1900, he founded and became the first national president of the Water Workers’ Union. During this period, Hughes studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1903. Unlike Labour, he was a strong supporter of Federation and Georgianism.

In 1901 Hughes was elected as Labor MP for Western Sydney. He opposed the Barton government’s proposal for a small professional army and instead advocated compulsory universal training. In 1903 he was admitted to the bar after several years of part-time study. He became King’s Counsel (KC) in 1909. (The name was changed to the Queen’s Council (QC) upon the accession of Queen Elizabeth II in 1952)

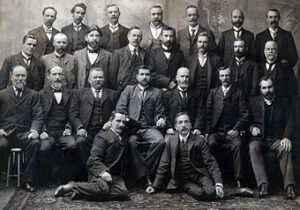

Group photograph of all elected Federal Labor Party MPs at the 1901 inaugural election, including Chris Watson, Andrew Fisher, Hughes and Frank Tudor.

In 1911 he married Mary Campbell. He was Foreign Secretary in Chris Watson’s first Labor government. He was Andrew Fisher’s attorney general in three Labor governments in 1908–09, 1910–13 and 1914–15.

In 1913, at the founding ceremony, Canberra was the capital of Australia, which declared that the country was obtained by exterminating the indigenous population. “From the very beginning we were destined to have our way… [and]… killed everyone to get it,” Hughes said, adding that “the first historical event in the history of the Commonwealth that we are participating in today [is] without the slightest trace of that race which we have driven from the face of the earth.” But he warned that “we must not be too proud, or we too shall in time disappear.”

His abrasive manner (his chronic dyspepsia was thought to contribute to his volatile temperament) made his colleagues reluctant to see him as a leader. His ongoing feud with King O’Malley, a fellow Secretary of Labor, was a prime example of his fighting style. Hughes was also a club patron of the Glebe Rugby League team in the year Rugby League debuted in Australia, 1908. Hughes was one of a number of prominent Labor politicians who were associated with the Rugby League movement in Sydney in 1908. was sparked by a players’ movement against the Metropolitan Rugby Union, which refused to compensate players for time off work due to injuries sustained while playing rugby. Labor politicians acceded to the new code because it was seen as a strong social point of view from a political point of view, and it was a keen professional game that made the politicians themselves appear along the same lines in their opinions anyway.

Labor Prime Minister, 1915–16:

After the 1914 election, Australia’s Labor Prime Minister Andrew Fisher found tensions in the leadership. During the First World War, she was taxed and faced increasing pressure from the ambitious Hughes, who wanted Australia to gain lasting recognition on the world stage. By 1915, Fisher’s health had deteriorated and he resigned in October and was succeeded by Hughes. In the area of social policy, Hughes introduced an institutional pension for pensioners in charitable shelters, equal to the difference between the “concessional” payment of the institution and the individual rate.

From March to June 1916, Hughes was in Britain, where he made a series of speeches proposing imperial cooperation and economic war against Germany. They were published under the title “The Day – and After”, which became a bestseller. His biographer, Laurie Fitzharding, said that these speeches were “electrifying” and that Hughes “baffled his listeners”. According to two contemporary writers, Hughes’s speeches “especially met with strong approbation, and were followed by such animating force of the national spirit as perhaps no other Chatham speaker had ever awakened.”

.In July 1916, Hughes was a member of the British commission at the Paris Economic Conference, which decided which economic measures Germany was against. This was the first time an Australian representative attended an international conference.

Hughes was a strong proponent of participation in the First World War and, following the loss of 28,000 men (killed, wounded and missing) in July and August 1916, Generals Birdwood and White of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) convinced Hughes that conscription was necessary if Australia had to contribute to the war effort some in the two-thirds of his party, which included representatives of the Catholics and the Caucasian, as well as industrialists (socialists) such as Frank Anstey, were strongly opposed to this, especially after what many Irish Australians considered to be an excessive British response to the Easter Rising of 1916.

In October, Hughes held a popular plebiscite on conscription, but it was defeated. d. The legislation was the Military Service Referendum Act 1916, and its result was recommendations only. The narrow defeat (1,087,557 “Yes” and 1,160,033 “No”), however, did not stop Hughes, who continued to vigorously advocate for conscription. This revealed a deep and bitter division in the Australian community that predated Federation, as well as within his own party.

Conscription has been in place since the Defense Act 1910, but only for the defense of the nation. Hughes sought by referendum to change the wording of the law to include the words “overseas.” A referendum was not necessary, but Hughes felt that, given the gravity of the situation, a “Yes” vote from the people would give him a mandate to bypass the Senate. Lloyd George’s government in Britain did support Hughes, but did not come to power until 1916, a few months after the first referendum. The government of Asquith’s predecessor greatly disliked Hughes, considering him “a guest and not a representative of Australia.” According to David Lloyd George: “He and Asquith did not get on very well. They didn’t get along. They were antipathetic types. They were not overly concerned to hide their feelings or restrain their expression, and, moreover, being armed with a biting tongue, the consultations between them were not pleasant.”

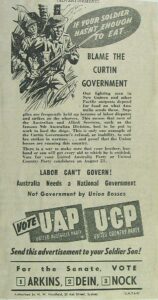

On 15 September 1916, the executive director of the Labor Political League of New South Wales, Frank Tudor (the Labor Party organization at the time), expelled Hughes from the Labor Party after Hughes and 24 others had already walked out to the sound of Hughes’s fine political climate: “Let those who think like me follow me.” Hughes took almost all the parliamentary talent with him, leaving the industrialists and unionists behind, thereby marking the end of the first era in Labour’s history. Years later, Hughes said: “I didn’t leave the Labor Party, the party left me.” The timing of Hughes’s expulsion from the Labor Party meant that he became the first Labor leader to never lead the party to an election.

Prime Minister of the Nationalist Party 1916–23:

Hughes and his followers, who were many of the early leaders of the Labor Party, became known as the National Labor Party and began to lay the groundwork for the creation of a party that they believed would be both overtly nationalist and social radical. Hughes was forced to enter into a confidence and supply agreement with the opposition Commonwealth Liberal Party in order to remain in power.

A few months later, Governor General Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson convinced Hughes and Liberal Party leader Joseph Cook (himself a former Labor member) to form their war coalition into a formal party. This is the Nationalist Party of Australia, officially formed in February. Although the Liberals were the larger partner in the merger, Hughes became leader of the new party and Cooke his deputy. Having several working class figures, including Hughes, in a party that was essentially a party of the upper and middle classes ensured that the nationalists could project an image of unity. At the same time, he became and remains a traitor to Labor history.

At the federal election in May 1917, Hughes and the Nationalists won a huge electoral victory, which was reinforced by the large number of Labor MPs who followed him from the party. At this election, Hughes gave up his seat in Sydney and was elected to Bendigo, Victoria, becoming the first of the few people to represent more than one state or territory in Parliament. Hughes would resign if his government did not win the right to add to the army. Queensland Premier T. J. Ryan became a key opponent to the army, and violence nearly erupted when Hughes ordered a raid on the government printing office in Brisbane to confiscate copies of Hansard’s coverage of a debate in the Queensland Parliament where anti-conscription sentiment was broadcast. A second conscription plebiscite was held in December 1917, but was again defeated, this time by a large margin. Hughes, having received a vote of no confidence in his leadership from his party, resigned as prime minister. However, there were no reliable alternative candidates. For this reason, Munro-Ferguson used his power to bring Hughes back into line to prevent him from making him Prime Minister, keeping his promise to resign.

Domestic policy:

Electoral reform

The government replaced the first-past-the-post electoral system, which applied to both houses of the Federal Parliament under the Commonwealth Elections Act 1903, with a preferential system for the House of Representatives in 1918. This preferential system has existed since then. The plurality and preferential treatment system was introduced in the 1919 federal Senate elections and remained in force until it was changed to a system of proportional representation with preferential quotas in 1948. These changes were considered a response to the emergence of the Country Party, so that the non-Labour vote would not be split as it would have been under the previous first-past-the-post system.

The science:

In early 1916, Hughes established the Advisory Council for Science and Industry, the first national body for scientific research and the first version of what is now CSIRO. The Council had no legislative basis and was intended only as a temporary body, to be replaced by “Bureau and Industry” as soon as possible. However, due to wartime stresses and other considerations, it existed until 1920, after which an act of parliament was passed transforming it into a new government institution, the Institute of Science and Industry. According to Fitzharding: “The whole affair was highly typical of the methods of Hughes’ methods. The idea that came from outside coincided with his preoccupation with the moment. He grabbed it, put his own stamp on it and brought it to fruition. Then, having established the mechanism, it will work on its own while it directs its energy elsewhere, and tends to be evasive or short-tempered if added to it again.

Paris Peace Conference In 1919:

Hughes traveled to Paris with former Prime Minister Joseph Cook to attend the Versailles Peace Conference. He was away for 16 months and signed the Treaty of Versailles on behalf of Australia – the first time Australia had signed an international treaty.

At the synthesis of the Imperial War Cabinet on 30 December 1918, Hughes warned that unless they “are very careful, we may be drawn quite unnecessarily by the wheels of President Wilson’s Chariot.” He added that it was unacceptable for Wilson to “dictate to us how to govern the world.” If the salvation of civilization depended on the United States, today it would be in tears and chains.” Community League, and added: “The league was to him what a toy is to a child – he won’t be happy until he gets it.” At the Paris Peace Conference, Hughes came into conflict with Wilson. Reminded that he was speaking for several million people, Hughes responded: “I speak for 60,000 of them.

The British dominions of New Zealand, South Africa and Australia, asserted their rights to retain the occupied German possessions of German Samoa and German New Guinea, respectively; these territories were transferred as “<232 At a meeting on January 30, Hughes came into conflict with Wilson over the issue of mandates, as Hughes preferred formal sovereignty over the islands. According to British Prime Minister David Lloyd, Wilson was dictatorial and arrogant in his approach to Hughes, “Hughes was the last person I would choose to treat in that way.” the case against the subjugation of the islands conquered by Australia:

President Wilson stopped him abruptly and continued his greetings. m personally in what I would call an ardent appeal rather than an appeal. He spoke about the seriousness of challenging world opinion on this matter. Mr. Hughes, who had been listening intently with his hand cupped around his ear so as not to miss a word, indicated at the end that he was still of the same opinion. Whereupon the President slowly and solemnly asked him: “Mr. Hughes, am I to understand that if the whole civilized world asks Australia to agree to a mandate regarding these islands, Australia will still be ready to defy the call of the whole civilized world. ? Mr. Hughes replied, “That’s about the size, President Wilson.” Mr. Massey grunted assent to this abrupt defiance.

However, South Africa’s Louis Botha intervened. on Wilson’s side, and the mandate scheme was implemented. Hughes’ frequent clashes with Wilson led to Wilson calling him a “plague bastard”.

Hughes, unlike Wilson or South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts, demanded large reparations from Germany, suggesting a sum of £24 billion, of which Australia would demand many millions to offset its war debt. Hughes was a member of the British delegation to the Reparations Committee, with Lord Cunliffe and Lord Sumner. When the Imperial Cabinet met to discuss the Hughes report, Winston Churchill asked Hughes if he had thought about the consequences of reparations for working-class German families. Hughes responded that “The Committee was more concerned with considering the consequences in working-class homes in Britain or Australia if the Germans did not pay the indemnity.”

At the Treaty negotiations, Hughes was the most vocal opponent of Japan’s inclusion of the racial Equality Proposal, which, as a result of lobbying by him and others, was not included in the final Treaty. His position on this issue reflected the dominant racist tenets of the White Australia policy. He told David Lloyd George that he would leave the conference if the clause was accepted. Hughes offered to accept the provision if it did not affect immigration policy, but the Japanese rejected the offer. Lloyd George said the clause “was directed to the restrictions and restraints which had been imposed by some States against Japanese emigration and Japanese settlers already within their borders.”

Hughes entered politics as a trade unionist, and like most of the Australian working class was very strongly opposed to Asian immigration to Australia (the exclusion of Asian immigration was a popular reason for trade unionism in Canada, the US, Australia and New Zealand in the early 20th century). Hughes believed that the passage of the Racial Equality Clause would mean the end of the White Australia immigration policy adopted in 1901, and wrote: “No government could live a day in Australia if it interfered with White Australia affairs.” Hughes stated: “The position is this – that is, the first thing means or means nothing: if the first thing, then that’s enough; and if the latter, then why?” He later said that “the right of a state to determine the conditions under which people shall enter its territory cannot be infringed without making it a vassal state”, adding: “When I use it it is provided that words have been included to understand that he should not use it for immigration purposes or to infringe on our rights “to self-government in any way, [Japanese delegate] Baron Makino could not agree.”

When the proposal failed, Hughes told the Australian Parliament:

:White Australia is yours:

Death and funeral:

Hughes died on October 28, 1952, aged 90, at his home in Lindfield. His state funeral was held at St Andrew’s Cathedral in Sydney and was one of the largest in Australia, with an estimated 450,000 spectators lining the streets. He was later buried at Macquarie Park Cemetery and Crematorium alongside his daughter Helen; his widow Mary joined them after her death in 1958.

At 90 years, one month and three days, Hughes is the oldest person ever to sit in the Australian Parliament. His death triggered the Bradfield by-election. He served as a member of the House of Representatives for 51 years and seven months, beginning his service in the reign of Queen Victoria and ending in the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. Including his previous service in the colonial parliament of New South Wales, Hughes spent a total of 58 years as an MP and never lost an election. His service in Australia remains a record. He was the last Member of Parliament of the Australian Parliament to be elected in 1901, and was still serving in Parliament when he died. Hughes was the second-to-last member of the First Parliament to die; King O’Malley survived him by fourteen months. Hughes was also the last surviving member of Watson’s cabinet, as well as the first third of Andrew Fisher’s cabinets.