BIOGRAPHY:

Boudicca (Boudica, Celtic Boudica, inaccurate Roman rendering Boadicea, Latin Boadicea) was the queen of the Celtic Iceni people, who lived in the territory of modern Norfolk in eastern Britain. Wife of Prasutagus. After the death of her husband, Roman troops occupied her lands, and Emperor Nero stripped her of her title. This forced Boudicca to lead the anti-Roman revolt of 61, in which several Celtic tribes united against the occupying power. Details about this uprising were preserved in the works of ancient writers Tacitus and Cassius Dio. These works were rediscovered during the Renaissance, but it was during the Victorian period that parallels were drawn between Victoria and Boudicca. Then she received the status of a national hero.

Boudicca died in 60 or 61 AD, probably by suicide.

Boudicca’s name:

Until the end of the 20th century, Boudicca was called Boadicea, which probably arose due to a copyist error when the work of Tacitus was copied in the Middle Ages. The name comes in many forms. Tacitus has the variants Boadicea and Boudicea. In the writings of Dio Cassius there are variants Βουδουικα, Βουνδουικα and Βοδουικα. The name is almost certainly originally Boudica or Boudicca, which is a proto-Celtic feminine adjective *boudīka (victorious), derived from Celtic *bouda (victory), Irish bua, Classical Irish buadh, Welsh Buddug. Similar names existed in Lusitania – spelling Boudica, in Bordeaux – Boudiga. The Gauls had a goddess Boudiga, who apparently was the goddess of victory, military success.

Based on the later development of Welsh and Irish, Kenneth Jackson suggested that the correct spelling in Breton is Boudica [bɒʊˈdiːkaː]. The closest equivalent to the first vowel is “ou” in the English bow. In modern English the name is pronounced [buːˈdɪkə].

Origin and family:

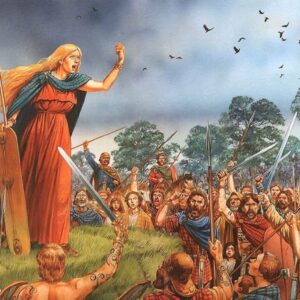

Both Tacitus and Dion believe that Boudicca was of royal origin. Dion claims that she was “smarter than most women, tall, had long red hair reaching to her hips, a rough voice and piercing eyes. She used to wear a large gold necklace (possibly spinning), a multi-colored tunic, and a thick cloak held together by a buckle.”

Boudicca was married to the Iceni tiger Prasutagus and bore him two daughters.

Queen and exile The Iceni lived in an area roughly corresponding to modern Norfolk. Their country was not originally part of the Roman Empire, but voluntarily entered into an alliance with Rome as allies after Claudius’s conquest of Britain in 43. In 47, the then governor Publius Ostorius Scapula tried to disarm them, but Prasutagus managed to defend his independence. He lived a long life in prosperity and, in order to maintain royal power for his family, made the Roman emperor heir along with his wife and two daughters.

It was the norm for Rome to grant independence to allied kingdoms only for the duration of the allied ruler’s life, and the allied ruler, in turn, agreed to cede the kingdom to Rome after his death. For example, in this way Rome annexed Bithynia and Galatia. Roman law allowed succession to the throne only through the male line. That is why, after the death of Prasutagus, his lands were taken away, his property was described, and power passed to Rome. Tacitus reported that Boudicca was flogged and her daughters raped. The treasury of Prasutagus was seized to pay off the debt, since he had huge debts to Seneca.

Boudicca’s Last Battle:

Suetonius grouped his forces in the West Midlands. The positions were surrounded on the flanks by forest. His forces numbered over 10,000 men, among whom were the XIV Legion, the Vexillarii of the XX Legion and many militia. However, Boudicca’s troops were several times larger than the forces of Suetonius and numbered, according to various estimates, from 80 thousand to 230 thousand people.

Tacitus writes that Boudicca controlled her troops from a chariot, and attributes to her a speech in which she asked to be considered not a noble queen avenging a lost kingdom, but an ordinary woman avenging her freedom taken away, her body beaten with whips, and her chastity violated. daughters. The gods were on their side, they had already defeated one legion that decided to resist them, and they would defeat others. She, a woman, would rather die than live as a slave, and besides, she called on her people.

However, the Romans, more skilled in open battles, countered numbers with skill. At the beginning of the battle, the Romans rained down thousands of darts on the Britons, who were rushing towards their ranks. Those Roman soldiers who had already gotten rid of the javelins broke up the second wave of the British offensive in dense phalanxes. After this, the phalanxes were formed into wedges, which struck from the front. Unable to withstand the onslaught, the Britons fled, but the path to retreat was blocked by convoys with their families. There, at the convoys, the Romans overtook the enemy and carried out a merciless massacre.

Tacitus writes that, seeing the defeat, Boudicca took the poison of black hemlock. According to Cassius Dio, she fell ill after the defeat and died soon after. According to both sources, her funeral was rich.

Reverence:

The figure of Boudicca was surrounded by a kind of romantic cult under the English queens Elizabeth and Victoria – not least because her name means “victory” (like the name Victoria). During the Victorian period, numerous sculptural images of the freedom-loving leader of the Iceni appeared.

The paradox is that the image of a “native” warrior who sacrificed herself in the fight against the greatest empire of her time was reinterpreted as a symbol of the British Empire – the largest empire in human history.

Emperor Nero:

This is how he tried to keep power for his children, but it didn’t work. In Rome, inheritance through the female line was not recognized and the daughters of the leader could not inherit him. That is, the Iceni and their territories became the full possession of the Roman Empire.

Immediately after the death of Prasutagus, the kingdom of the Iceni was annexed, the lands were confiscated, and the property was described. Also, to pay off the debt, the entire treasury of Prasutagus was seized. It turns out he owed a huge amount to Seneca.

Added to this was the personal tragedy of Boudicca and her daughters. When the queen tried to object to the Roman officials, she was publicly flogged on the scaffold, and there, while she was unconscious, both of her daughters were publicly raped.

And if before this Boudicca, in general, did not really protest, but simply tried to soften some aspects of the annexation, then she did not forgive the dishonor of her daughters and personal insult.

Insurrection:

It must be said that Celtic noble women were no match for Roman ones. They all had excellent command of weapons and were trained in military affairs. Boudicca was like that. And in 61, taking advantage of the situation when the Romans were campaigning on the island of Anglesey, the Iceni, led by Boudicca, the heir of her husband, rebelled against Roman rule. This uprising was supported by many Celtic tribes, Boudicca’s propaganda achieved its goal. Here is a quote from the Roman historian Tacitus:

“Boudicca, placing her daughters in front of her on a chariot, when she approached one or another tribe, exclaimed that … she was taking revenge not for the lost kingdom and wealth, but as a simple woman for the freedom taken away, for her body beaten with whips, for her desecrated chastity daughters.”

She managed to gather a huge army for those times and seriously threaten Roman rule. The city of Camolodun (modern Colchester) was taken and completely razed to the ground, and the IX Legion, which tried to recapture the city, was completely defeated and fled to Gaul.

Londinium (modern London), founded by the Romans in 43, fell next. Moreover, it was burned to the ground, and all its inhabitants were killed. The next city to be destroyed was Verulamium (modern St. Albans). The inhabitants were also killed and no prisoners were taken. To take revenge is to take revenge.

But the Romans also quickly found their bearings. The governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, quickly curtailed all other campaigns, gathered all his forces and grouped them in the territory of the modern West Midlands. There the decisive battle took place. The exact location is really unknown.

The balance of power was bad for the Romans. The Celts outnumbered the Roman army by an order of magnitude. However, it must be said that in that era there were no rivals equal to the Roman legions in open battle anywhere.

The result of the battle was quite predictable. The Celts were completely defeated and few escaped. According to contemporaries, their losses amounted to about 80,000 people, and the Romans lost only about 400 soldiers.

This, of course, is most likely a strong exaggeration, but the fact remains – the uprising was completely suppressed, and the rebel army was defeated. And Boudicca herself committed suicide by taking deadly poison. The fate of her daughters is unknown.

This is Boudicca, a woman who did not forgive humiliation and insult and managed to take revenge.

Archaeological Facts:

In February 2015, during excavations in the area of Bridges Garage, the area around the western gate of Roman Corinium, the town where modern Cirencester is located, a tombstone was discovered that can be dated to the early 2nd century. The epitaph on this tombstone is dedicated to a certain Bodication, who lived for 27 years. The tombstone, unfortunately, was not found at the burial site of this Bodication. It was used as a gravestone in a late Roman male inhumation burial, with the side with the text and decoration placed inside, so that the text and decorative patterns were opposite the face of the deceased, which in itself probably speaks of some interesting late Romano-British funeral tradition.

The plate itself is also quite interesting. The arrangement of the inscriptions seems to suggest that the text is not finished. Apparently, the customer, most likely a husband or other close relative, planned to join Bodication in the foreseeable future and left a place where his name and other information important for this type of monument would be inscribed. But that did not happen. In addition, the monument contains an image of the Ocean, a sea deity, which is very rare for tombstones. This probably reflected the influence of local, pre-Roman religious traditions, since the Ocean is often found in the sculpture and mosaics of Corinius. The face of the sea god was knocked down over time, which could, in turn, serve as a sign of some kind of religious change or, perhaps, even a struggle between Christians and pagans.

But this question is far beyond the scope of the study of Boudicca and Bodication. We can say with a fair degree of confidence that Bodication belonged to the middle strata of the community living in the Corinia region, or to the local elites, it’s difficult to say for sure. Her relatives had enough resources to order the production of an expensive monument.

At the same time, of course, the most important thing for us is the name of the deceased – Bodication. It is quite obvious that it is of British origin and is related to the name of the leader of the Iceni. What could this mean? That we should take a closer look at the lands where the tombstone was discovered. In Roman times they were united in the district of the Dobunnians, and modern historiography, following this administrative Roman tradition, designates the Britons of this region as the Dobunnians. At the same time, in the ancient tradition, in particular in Cassius Dio, the British tribe of the Bodunns is mentioned, who are quite logically identified with the Dobunnians. Usually the word “Dobunny” is used as the main and correct ethnonym, but it cannot be ruled out that the original name of the community was “Hangover”. The consonance of this ethnonym and the name Boudicca may indicate her connection with this region.

As we understand, in this situation there are obvious problems with the ethnonym itself. How exactly to reconstruct and read it correctly? However, it is worth keeping in mind that this is not the end of the interesting evidence from the lands of the Dobunn. It is important that some parallels and similarities can be traced in the material culture of the Pre-Bunnian and Iceni elites. However, these communities were not neighbors. The Dobunn occupied the territories of Gloucestershire and North Somerset, while the Iceni’s areas were in Norfolk, in the east of England. Nevertheless, researchers of British numismatics note a number of similarities in the legends of coins and images that both the Pre-Bunn and Iceni rulers used in their coinage.

Moreover, several coins from the end of the 1st century BC were found. e., on which the image of a horse and the name of a certain Boduok appear. Perhaps this is not the full name, but only part of it. Boduok’s coinage stands out from other Dobunni coins, leading some researchers to believe that he came from another British community, perhaps the Catuvellaunians, and perhaps the Iceni. However, in this situation, researchers suffer from a certain lack of numismatic data. Probably, the finds of new coins may somewhat change our ideas about both the Pre-Bunnian coinage and the Iceni coinage.

But in general, the available data collectively indicate that in the British communities, which were usually designated by the ethnonym “Dobunni,” names similar in root and sound to the name Boudicca were popular. In addition, the available evidence suggests that the Pre-Bunnian and Iceni elites had connections that were not hampered by the distances that separated their lands. It is likely that representatives of these elites entered into dynastic alliances and marriages, seeking to strengthen their power within the community and reputation outside it. Unfortunately, little is generally known about the nature of such practices in pre-Roman Britain. But an appeal to Gallic and Germanic material shows that their very existence is more than likely.