BIOGRAPHY:

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (lat. Gaius Iulius Caesar Augustus Germanicus), better known by his agnomen (nickname) Caligula (lat. Caligula). Born on August 31, 12 in Anzia – died on January 24, 41 in Rome. Roman Emperor since March 18, 37, the third of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, who went down in history as Caligula, was born on August 31, 12 in the city of Antium. He was the third of six children of Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder. When he was a child, his father took him with him on his famous German campaigns, where Guy wore children’s boots like army caligas. Because of this, the nickname “Caligula” was subsequently assigned to him, i.e. “boot” (Latin caligula – diminutive of caliga), which he did not like. Due to the deteriorating relationship between his mother and his great-uncle Tiberius following the mysterious death of Germanicus, Guy was sent to live first with his great-grandmother Livia and, after her death, with his grandmother Antonia. After the praetorian prefect Sejanus left the political scene, Guy, at the direction of Tiberius, began to live with him in his villa on Capri until the beginning of his reign. In 33, Caligula married Junia Claudilla, the wedding took place in Antium. However, both the child and Junia herself died during childbirth. It was said that the new praetorian prefect Macro offered Gaius his wife, Ennia Thrasilla, in return. Philo of Alexandria agrees with this version, Suetonius says that Gaius seduced her. On Capri, Caligula met Julius Agrippa.

The rise to power of Caligula:

Before his death, Tiberius declared Caligula and the son of Drusus the Younger, Tiberius Gemellus, equal heirs, but indicated that Caligula should replace him, although, according to Philo, he knew that he was unreliable. Despite the fact that Caligula did not understand administration, rumors soon appeared that he either strangled, drowned, or poisoned Tiberius, although he died of natural causes. According to other sources, Tiberius was strangled by Macron. Caligula arrived in Rome on March 28 and received from the Senate the title of Augustus, which had been revoked by Tiberius. Using the support of Macron, he achieved the title of princeps. At the beginning of his reign, Guy demonstrated piety. Quite unexpectedly, he sailed to Pandataria and Poncia, to the places of exile of his mother Agrippina and brother Nero. He transported their ashes to Rome and buried them with full honors in the mausoleum of Augustus. Apparently, in order to dispel gossip, Guy paid honor to the deceased Tiberius, paid the praetorians 2 thousand sesterces and, having compensated for the damage caused by the imperial tax system, reduced the taxes themselves and paid off the debts of previous emperors. This was followed by the abolition of the lese majeste law (lex de maiestate) and a political amnesty. However, after 8 months, Caligula unexpectedly fell ill with something (presumably encephalitis, according to Suetonius – epilepsy, which caused organic brain damage; according to another version, mental experiences of childhood affected).

After recovery, Guy’s behavior changed dramatically, although there is an opinion that some primary sources (mainly Suetonius and Tacitus, who were not critical enough of gossip and palace intrigue) exaggerated the situation. The dynastic element began to be openly demonstrated – the princeps’ sisters appeared on the coins: Drusilla, Livilla and Agrippina with a cornucopia, a cup and a steering oar, that is, with the attributes of the goddesses of fertility, harmony and Fortune. Caligula’s grandmother, Antonia, received not only the title of Augusta, but she, like the princeps’ three sisters, was given the honorary rights of Vestal Virgins, and their names were included in the vows and imperial oath. In 38, Caligula forced first Macron to commit suicide, then the father of his first wife, Marcus Junius Silanus, and later executed Gemellus for an allegedly suspicious attitude towards Caesar (at one of the feasts, Caligula claimed that Gemellus smelled of an antidote).

The reign of Caligula:

According to Suetonius, he constantly repeated and was guided by the expression “Let them hate, as long as they fear” (lat. Oderint, dum metuant). In Rome, Caligula began building the Aqua Claudia and Anio Novus aqueducts. To improve the supply of grain, which had caused revolts under Tiberius, the harbor at Rhegium was improved. Due to the bias of the main sources, the main content of Caligula’s domestic policy is usually considered to be the confrontation with the Senate. However, at the beginning of his reign, the new emperor treated the Senate very moderately, emphasizing in every possible way his respect for the senators and his desire to cooperate with them. The lack of authority of the new emperor affected the softness of the beginning of his reign: he, a newcomer to public life, had to pursue a liberal policy aimed at gaining popularity in the Senate and the people. Unlike his predecessors, Caligula was consul almost every year – in 37, 39, 40 and 41. Although this was a departure from the unwritten traditions of dual power (coexistence and co-government of the emperor and the Senate) established by Octavian Augustus, Caligula had reasons to do so. Before taking the imperial throne, he was a private person and held only minor government positions, so his authority (Latin auctoritas) in politics was negligible. Regular posting of the post of consul could help him increase his authority and make the Senate forget about his youth and inexperience. At the beginning of his reign, Caligula repealed the law on lese majeste introduced by Octavian Augustus (Latin: lex de maiestate; lex maiestatis), which Tiberius used to fight real and imaginary opponents. The new emperor had personal reasons for repealing this extremely unpopular law, since its selective application by Tiberius led to the exile and, subsequently, the death of Caligula’s mother and brothers. A complete amnesty and rehabilitation was declared in all cases of lese majeste, and he allowed everyone who had been convicted and exiled from Rome to return to the capital. Caligula did not pursue informers and prosecution witnesses in these cases, for which purpose he publicly burned in the Forum all documents related to these trials (they were kept by Tiberius), and also swore that he had not read them. However, Cassius Dio writes that Caligula kept the originals and burned copies, and modern researchers share the skepticism of the ancient historian.

In 38, Caligula returned to the people the right to elect certain magistrates, which Tiberius transferred to the Senate (the people’s assembly retained the purely ceremonial function of formally approving the appointments made). Various reasons are cited that could have prompted Caligula to return to the republican electoral system. The competition between candidates for high positions could have been intended by the emperor as an incentive for candidates to hold various entertainment events, which could shift part of the burden from the treasury onto the shoulders of private individuals. However, the practical significance of this measure was small, since the emperor retained the right to nominate candidates and vouch for applicants for positions. As a result, the practice of distributing seats, in which all candidates for magistrates in the required number were approved in advance, was retained. A return to the traditional electoral procedure did not enjoy the support of senators, who were accustomed to controlling the confirmation of magistrates and therefore sabotaged the reform.

The popular vote did not take root in the new conditions, and already in 40 Caligula returned to the system of approving magistrates in the Senate. In addition to the lack of real competition, Cassius Dio sees the reason for the failure of this reform as the changed psychology of the Romans, who were unaccustomed to real elections or had never participated in them, and therefore did not take them seriously: “But since the latter [citizens] became rather indifferent to the performance of their duties, since for a long time they did not participate in public affairs, as befits free people, and since, as a rule, no more applicants sought public office than needed to be elected (and if in some case there were more than this number, then they settled the matter among themselves), only the appearance of democracy was preserved, but in reality it did not exist at all.” The final abolition of the elections of magistrates showed the political flexibility of the emperor, who was not afraid to cancel the failed reform. Caligula took several more measures concerning the Senate. The emperor consolidated the traditional order of speech when voting in the Senate, modified by Tiberius. The reasons for this reform are unclear. The point of view of Dio Cassius, who believes that Caligula wanted to take away the right of first vote from Marcus Junius Silanus, is not supported. After this reform, Caligula himself began to speak last in discussions, and senators could no longer limit themselves to simply supporting the opinion of the emperor. Among the last to speak out was Claudius, and Suetonius considers this situation to be a consequence of the emperor’s personal hostility. Caligula also forced senators to take an annual oath. The purpose of this measure is unclear, and it is assumed that in this way Caligula reminded the senators of his primacy. A private measure designed to show the new emperor’s concern for senators was allowing them to take cushions with them to circus performances so as not to sit on bare benches. The liberalization of domestic policy at the beginning of Caligula’s reign also affected other areas of public life – as a rule, he abolished the repressive measures taken by Tiberius. The works of Titus Labienus, Cremutius Cordus and Cassius Severus, prohibited by Tiberius, were not only allowed, but also received the support of the emperor in distributing the few surviving copies. Caligula is credited with the idea of prohibiting the works of Virgil and Titus Livy, but this message from Suetonius may be incorrect, since it directly contradicts the permission of the works of Labienus, Cremutius Cordus and Cassius Severus. Caligula allowed the activities of guilds (non-political associations of Roman citizens), which had been prohibited by his predecessor. The guilds were subsequently closed again by Claudius. Finally, the new emperor restored another feature of public life that had been abolished by Tiberius, again beginning to publish reports on the state of the empire and the progress of state affairs. In this case, Claudius also returned to the practice adopted under Tiberius.

The popular vote did not take root in the new conditions, and already in 40 Caligula returned to the system of approving magistrates in the Senate. In addition to the lack of real competition, Cassius Dio sees the reason for the failure of this reform as the changed psychology of the Romans, who were unaccustomed to real elections or had never participated in them, and therefore did not take them seriously: “But since the latter [citizens] became rather indifferent to the performance of their duties, since for a long time they did not participate in public affairs, as befits free people, and since, as a rule, no more applicants sought public office than needed to be elected (and if in some case there were more than this number, then they settled the matter among themselves), only the appearance of democracy was preserved, but in reality it did not exist at all.” The final abolition of the elections of magistrates showed the political flexibility of the emperor, who was not afraid to cancel the failed reform. Caligula took several more measures concerning the Senate. The emperor consolidated the traditional order of speech when voting in the Senate, modified by Tiberius. The reasons for this reform are unclear. The point of view of Dio Cassius, who believes that Caligula wanted to take away the right of first vote from Marcus Junius Silanus, is not supported. After this reform, Caligula himself began to speak last in discussions, and senators could no longer limit themselves to simply supporting the opinion of the emperor. Among the last to speak out was Claudius, and Suetonius considers this situation to be a consequence of the emperor’s personal hostility. Caligula also forced senators to take an annual oath. The purpose of this measure is unclear, and it is assumed that in this way Caligula reminded the senators of his primacy. A private measure designed to show the new emperor’s concern for senators was allowing them to take cushions with them to circus performances so as not to sit on bare benches. The liberalization of domestic policy at the beginning of Caligula’s reign also affected other areas of public life – as a rule, he abolished the repressive measures taken by Tiberius. The works of Titus Labienus, Cremutius Cordus and Cassius Severus, prohibited by Tiberius, were not only allowed, but also received the support of the emperor in distributing the few surviving copies. Caligula is credited with the idea of prohibiting the works of Virgil and Titus Livy, but this message from Suetonius may be incorrect, since it directly contradicts the permission of the works of Labienus, Cremutius Cordus and Cassius Severus. Caligula allowed the activities of guilds (non-political associations of Roman citizens), which had been prohibited by his predecessor. The guilds were subsequently closed again by Claudius. Finally, the new emperor restored another feature of public life that had been abolished by Tiberius, again beginning to publish reports on the state of the empire and the progress of state affairs. In this case, Claudius also returned to the practice adopted under Tiberius.

Caligula’s reforms:

With the light hand of Suetonius, the opinion was established about the extraordinary wastefulness of Caligula, which allegedly led to a catastrophic deterioration in the financial situation of the empire. However, in the 20th century, many researchers revised this point of view. First of all, the sources do not write anything about an acute shortage of money at the beginning of the reign of the next emperor, Claudius. Moreover, the latter arranged very generous payments to the Praetorians, many times higher than similar handouts to Caligula. Back in January 41, coins were minted from precious metals, which would have been impossible if the treasury was empty, as Suetonius claims. Finally, Caligula voluntarily resumed the publication of reports on the state of the empire, from which contemporaries could clearly trace the deterioration of the financial situation of the empire. The traditionally wasteful Caligula is contrasted with the stingy Tiberius, but it was the new emperor who had the responsibility to fulfill a number of unpaid debt obligations and continue the mothballed construction projects of his thrifty predecessor. Caligula abolished the sales tax (centesima rerum venalium) introduced by Octavian Augustus, which Tiberius reduced from 1% to 0.5%, but then returned to the full rate. Apparently, the tax abolition was welcomed by wealthy Italians. This measure was widely advertised on the new coins. It is assumed that in order to replenish the treasury, Caligula executed Ptolemy, the ruler of Mauretania, which led to the annexation of his puppet state to the Roman Empire. Some confusion surrounds Caligula’s introduction of new taxes in 40, since it contradicts the slightly earlier abolition of the sales tax. “He collected new and unprecedented taxes – first through tax farmers, and then, since it was more profitable, through praetorian centurions and tribunes. Not a single thing, not a single person was left without tax.

A flat duty was levied on everything edible that was sold in the city; from every court case, a fortieth part of the disputed amount was collected in advance, and those who retreated or agreed without trial were punished; porters paid an eighth of their daily wages; prostitutes – the price of one intercourse; and to this article of the law it was added that everyone who had previously engaged in fornication or pimping was also subject to such a tax, even if they had since entered into a legal marriage. Taxes of this kind were announced orally, but not posted in writing, and due to ignorance of the exact words of the law, violations were often committed; Finally, at the request of the people, Guy posted the law, but wrote it so small and hung it in such a cramped place that no one could copy it,” writes Suetonius. For the Romans, these innovations were unprecedented, since full citizens did not pay direct taxes. The emperor’s actions seem illogical, and they are trying to explain them either through an awareness of his wastefulness, or by criticizing the sources: Suetonius allegedly seriously exaggerated the scope of the new taxes. The abolition of most of them by Claudius does not help clarify the content and size of the new measures. Caligula’s successor retained only the tax on prostitutes.

A flat duty was levied on everything edible that was sold in the city; from every court case, a fortieth part of the disputed amount was collected in advance, and those who retreated or agreed without trial were punished; porters paid an eighth of their daily wages; prostitutes – the price of one intercourse; and to this article of the law it was added that everyone who had previously engaged in fornication or pimping was also subject to such a tax, even if they had since entered into a legal marriage. Taxes of this kind were announced orally, but not posted in writing, and due to ignorance of the exact words of the law, violations were often committed; Finally, at the request of the people, Guy posted the law, but wrote it so small and hung it in such a cramped place that no one could copy it,” writes Suetonius. For the Romans, these innovations were unprecedented, since full citizens did not pay direct taxes. The emperor’s actions seem illogical, and they are trying to explain them either through an awareness of his wastefulness, or by criticizing the sources: Suetonius allegedly seriously exaggerated the scope of the new taxes. The abolition of most of them by Claudius does not help clarify the content and size of the new measures. Caligula’s successor retained only the tax on prostitutes.

Modern researchers note that the measures to increase the number of taxes mentioned by Suetonius were new for Rome, but similar taxes had long been established in Egypt. Some of Caligula’s activities led to a revival of the economy. Thus, large-scale construction work pumped money into the economy and created new jobs. Trimalchio from Petronius’s Satyricon supposedly became rich during the reign of Caligula, when “wine was valued on a par with gold”, which apparently has a real prototype in the growth of demand for luxury goods. Large-scale distributions of money at the beginning of the reign of the new emperor also contributed to the revival of the economy. Coinage under Caligula underwent several changes. Apparently, it was on his initiative that small mints in Spain were closed. The main mint was moved from Lugdunum to Rome, which increased the influence of the emperor on coinage. The value of this decision is evidenced by its preservation by successors. Apparently, coins were minted most actively at the very beginning of Caligula’s reign to ensure mass distribution. In addition, for some unclear reasons, neither gold nor copper coins were minted in 38, and subsequently relatively few gold and silver coins were issued. In general, the emperor’s policy took into account the crisis of 33, when a cash shortage began in Rome, and the measures taken prevented a repetition of these events. Caligula tried to adjust the complex multi-metal system of monetary units by making the dupondium (2 asses coin) heavier so that it would be more different from the asses, but Claudius abandoned this experiment. The late 1st century poet Statius once used the expression “for about the price of Gaius [Caligula’s] ass” (plus minus asse Gaiano) to mean “very cheap”, “for a penny”, but the connection of this phrase with Caligula’s monetary policy is unclear. Several innovations marked the appearance of the coins. In particular, for the first time a coin was minted with a scene of the emperor addressing the troops. After Caligula’s assassination, the new emperor Claudius ordered the bronze coins minted by Caligula to be melted down. Statius’ testimony suggests that at least some of the coinage from Caligula’s time remained in circulation. However, coins minted under Caligula are quite rare in most surviving hoards. On small coins of Caligula, they were often stamped with the initials of Claudius (TICA – Tiberius Claudius Augustus), with which Caligula’s initials were stamped; on others, a portrait of Claudius was stamped over Caligula’s profile; on others, Caligula’s initials were knocked out, and on others, the portrait of this emperor was deliberately spoiled.

Caligula’s military campaigns:

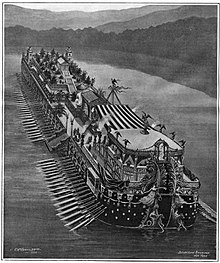

Deciding to continue his father’s work, Caligula, despite learning about Getulik’s conspiracy, organized a German campaign. The day before, in 39, a new legion XV Primigenia was created for reinforcement, the allied Batavians were added to the cavalry, and already in the fall Caligula with his sisters Julia Agrippina and Julia Livilla, his personal guard and two legions crossed the Alps and reached the Middle Rhine, where, near the modern Military operations began in Wiesbaden. In the winter of 39/40 a fort was built, called the Praetorium of Agrippina (now Valkenburg). A little later, Caligula, during his trip to Lugdunum, visited the military base of Fection (Vechten). His personal presence there was proven by the discovery of wine from the imperial cellars. Presumably at this time Caligula used the informal titles Castorum Filius (“Son of the Camp”) and Pater Exercituum (“Father of the Army”). A new fort was built on the Lower Rhine, Laurium, which Caligula used for a campaign against the Chauci, during which the military leader Publius Gabinius Secundus was able to recapture the standard of one of the legions defeated in the Teutoburg Forest. That same year, several Hutts were captured and a new military award was established – the corona exploratoria. Nevertheless, primary sources say that the short-lived campaign on the eastern bank of the Rhine led to a stalemate. In 40, the construction of a long chain of limes began in Lower Germany, which was continued in 47 by Corbulo. In February-March 40, Caligula began to prepare for a campaign in Britain. According to various estimates, from 200 to 250 thousand soldiers were collected. However, the troops, having reached the coast of the English Channel, stood up, siege and throwing engines were installed along the coast – having ordered the battle signal, Caligula for some reason ordered the legionnaires to collect shells and shells in their helmets and tunics, as a “gift of the ocean.” However, this version is disputed, since the word concha, which Caligula used in the order to collect shells, also denoted small light ships, which suggests that the troops had to prepare for the crossing (which in turn implies that siege and throwing engines , placed along the shore, were actually ship’s). It was necessary to fight with the ships of the Britons. The version is indirectly strengthened by the statement of Suetonius.

The campaign paused and was carried out by Claudius. However, Admin, the son of the Catuvellaunian leader Cunobelinus, expelled from Britain for his pro-Roman views, found refuge at the court of Caligula. Caligula, meanwhile, in his characteristic manner, executed Getulik and his brother-in-law Marcus Aemilius Lepidus for a failed plot, and sent his two surviving sisters into exile. However, he maintained the warmest relationship with Drusilla, demanded divine honors for her and allegedly even committed incest with her. The death of Drusilla on June 10, 1938 was a great tragedy for Guy. He composed an obituary, which was read by Lepidus, and retired to his villa in Alba, and then to Campania and Sicily, letting his hair and beard grow as a sign of mourning (Latin: iustitium). At the end of the mourning, preparations began to celebrate the anniversary of Caligula’s first consulate. In the East, being bound by friendly ties with the kings of the client Hellenistic states, Caligula returned to a form of indirect rule. In the Balkans, Asia Minor, Syria and Palestine, ephemeral puppet states were created for his friends. Herod Agrippa, grandson of Herod the Great, received the title of king and the two old Jewish tetrarchies. In Thrace, Octavian Augustus divided power between the brothers Cotis and Rhescuporis, but after the latter attempted to seize sole power, he removed him and divided power between the sons of the two rulers. Cotys’s three children – Remetalcus III, Polemon and Cotys II – were sent to Rome, and in their place southern Thrace was ruled by Tiberius’ protege Titus Trebellienus Rufus. In the capital, the future emperor became friends with the children of Kotis.In 38, he gave Remetalka Thrace, where the son of Rheskuporidas had recently died, Polemon – Pontus and Bosporus, and Cotis received Lesser Armenia. Commagene, which Tiberius made a province, Caligula handed over to Antiochus IV along with part of Cilicia. The appointments were not random, since the new rulers were relatives of the previous ones. In addition to the rights to the throne themselves, the new rulers received generous financial support from Caligula – for example, Antiochus IV received 100 million sesterces. This amount is probably overestimated, but most likely it is based on the actual fact of paying the new ruler a one-time benefit. Subsequently, Caligula’s opponents accused his eastern friends of being responsible for the emperor’s despotic actions, but this was certainly not the case. Caligula’s appointments partly continued the policy of Augustus – to use dependent rulers where their presence was justified. At the same time, they came into conflict with the tendency to transform dependent territories into provinces (Commagene under Tiberius, Lycia and Rhodes under Claudius). In early 37, the governor of Syria, Vitellius, headed south to help the tetrarch of Galilee and Perea, Herod Antipas, invade the Nabataean kingdom. In Jerusalem, Vitellius learned of the death of Tiberius and stopped, awaiting instructions from the new emperor. Caligula took the opposite position in relation to the Nabateans and strongly supported their ruler Aretas IV. The reason for such a warm relationship was probably the help that Aretha provided to Caligula’s father. The hostility towards Herod Antipas, caused by the emperor’s friendship with Herod Agrippa, who was laying claim to power in Judea, also played a role. Around 40, Caligula executed the ruler of Mauretania, Ptolemy, who was invited to Lugdunum, and annexed his possessions to the Roman Empire (according to another version, the annexation was already formalized by Claudius). The reasons for the execution of Ptolemy, who was a distant relative of Caligula, are unclear, especially after the warm reception. Cassius Dio calls the wealth of this ruler the reason for the murder, but there is no other evidence of his wealth, and Caligula, on the contrary, preferred to give money to other dependent rulers rather than take it away. However, this version is usually preferred. Suetonius preserved another version: supposedly the emperor decided to execute Ptolemy because he appeared at gladiator fights in a very beautiful purple cloak. Trying to find a rational grain in this message, John Balsdon suggested that Caligula could have prohibited dependent rulers from wearing purple clothing, which emphasized royal dignity, in the presence of the Roman emperor. If this was indeed the case, then Caligula abandoned Tiberius’ liberal attitude on this issue and returned to the hard line pursued by Octavian Augustus. The third version is also associated with the “madness” of the emperor and lies in Caligula’s desire to take the place of the high priest of the cult of Isis. Finally, Caligula may have feared his distant relative Ptolemy as a dangerous rival. In support of this version, there is a connection between one of the leaders of the conspiracy against Emperor Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Getulik with the Mauretanian ruler – his father was the proconsul of Africa and made friends there with King Juba II, the father of Ptolemy.

The reasons for the annexation of Mauretania, in contrast to the execution of Ptolemy, are exclusively rational. First of all, this is the need to protect Roman Africa from the west, which Ptolemy could not cope with. During the Roman era, Africa had many fertile lands and was an important supplier of grain for Rome. In addition, Octavian Augustus founded 12 Roman colonies in the western Mediterranean coast of Africa, which were not formally part of Mauretania, but were not organized into a separate province and were controlled from Spain (Betica). Thus, the annexation of Mauretania is characterized as a completely sensible step. However, soon an anti-Roman uprising began in Mauretania, led by Edemon. Sam Wilkinson emphasizes that the causes of the uprising are not well known, and therefore its connection with the execution of Ptolemy, unpopular in some parts of his state, may be erroneous. It is assumed that it was Caligula who came up with the idea of dividing Mauretania into two provinces – Mauretania Caesarea and Mauretania Tingitana, although Dio Cassius attributes this initiative to Claudius. The difficulties in organizing the provinces during the uprising force us to listen specifically to the testimony of Dio Cassius. In the province of Africa Proconsular, neighboring Mauretania, at the beginning of Caligula’s reign, one legion was stationed, which was administered by the proconsul.

The new emperor transferred command to his legate, thereby depriving the Senate of control over the last legion. During the reign of Caligula, the first person from Africa appeared in the class of Roman horsemen. It was largely thanks to the actions of Caligula in Roman Africa that the preconditions were laid for the prosperity that came in the 2nd century. Immediately after coming to power, Caligula reconsidered relations with Parthia, the only influential neighbor of the Roman Empire and a rival in the struggle for influence in the Middle East. The Parthian king Artaban III was hostile to Tiberius and was preparing an invasion of the Roman province of Syria, but through the efforts of its governor Vitellius, peace was achieved. According to Suetonius, Artabanus showed respect for Caligula when he “gave honor to the Roman eagles, the badges of the legion, and the images of the Caesars.” He gave his son Darius VIII as a hostage to Rome. Perhaps as a result of negotiations between Rome and Parthia, Caligula moved away from the policies pursued by Augustus and Tiberius and voluntarily weakened Roman influence in disputed Armenia. To do this, he recalled Mithridates, who ruled there, appointed by Tiberius, imprisoned him and did not send him a replacement. However, the warming of Roman-Parthian relations was not least caused by civil strife in Parthia. Evidence from sources about Caligula’s activities in leading the provinces and dependent states is represented by the negative reviews of Josephus, Seneca and Philo about the poor state of the provinces after the death of the emperor. At the same time, Seneca’s data, John Balsdon believes, is extremely biased due to the author’s desire to please the new emperor Claudius, and the information of Josephus and Philo applies only to Judea and part of Egypt – Alexandria. A critical attitude towards sources on this issue is not shared by all researchers. As a result, assessments of Caligula’s provincial policies range from negative, focusing on the emperor’s inconsistency and failures, to positive, recognizing his competence in leading the empire. The assessments of individual episodes of his management of the provinces and dependent states also differ diametrically. Thus, Howard Scullard sees the complicating situation in Judea as a manifestation of the emperor’s recklessness, and Sam Wilkinson believes that against the general background of the turbulent history of Judea in the 1st century BC. e. The reign of Herod Agrippa can be considered a relatively calm period. Most researchers, however, agree on the recognition of miscalculations in relations with Mauretania, which led to the uprising. Caligula’s personnel appointments in the East are usually considered successful.

The new emperor transferred command to his legate, thereby depriving the Senate of control over the last legion. During the reign of Caligula, the first person from Africa appeared in the class of Roman horsemen. It was largely thanks to the actions of Caligula in Roman Africa that the preconditions were laid for the prosperity that came in the 2nd century. Immediately after coming to power, Caligula reconsidered relations with Parthia, the only influential neighbor of the Roman Empire and a rival in the struggle for influence in the Middle East. The Parthian king Artaban III was hostile to Tiberius and was preparing an invasion of the Roman province of Syria, but through the efforts of its governor Vitellius, peace was achieved. According to Suetonius, Artabanus showed respect for Caligula when he “gave honor to the Roman eagles, the badges of the legion, and the images of the Caesars.” He gave his son Darius VIII as a hostage to Rome. Perhaps as a result of negotiations between Rome and Parthia, Caligula moved away from the policies pursued by Augustus and Tiberius and voluntarily weakened Roman influence in disputed Armenia. To do this, he recalled Mithridates, who ruled there, appointed by Tiberius, imprisoned him and did not send him a replacement. However, the warming of Roman-Parthian relations was not least caused by civil strife in Parthia. Evidence from sources about Caligula’s activities in leading the provinces and dependent states is represented by the negative reviews of Josephus, Seneca and Philo about the poor state of the provinces after the death of the emperor. At the same time, Seneca’s data, John Balsdon believes, is extremely biased due to the author’s desire to please the new emperor Claudius, and the information of Josephus and Philo applies only to Judea and part of Egypt – Alexandria. A critical attitude towards sources on this issue is not shared by all researchers. As a result, assessments of Caligula’s provincial policies range from negative, focusing on the emperor’s inconsistency and failures, to positive, recognizing his competence in leading the empire. The assessments of individual episodes of his management of the provinces and dependent states also differ diametrically. Thus, Howard Scullard sees the complicating situation in Judea as a manifestation of the emperor’s recklessness, and Sam Wilkinson believes that against the general background of the turbulent history of Judea in the 1st century BC. e. The reign of Herod Agrippa can be considered a relatively calm period. Most researchers, however, agree on the recognition of miscalculations in relations with Mauretania, which led to the uprising. Caligula’s personnel appointments in the East are usually considered successful.

A serious difference between Caligula and his predecessors was the opening of the equestrian class to provincials. Subsequently, the policy of involving provincial elites in Roman society continued. In foreign policy, Caligula achieved lasting peace with Parthia and strengthened the position in remote regions by appointing loyal rulers. These actions gave the Roman Empire the opportunity to prepare for an offensive policy in the north. Confirmation of the reasonable nature of his foreign policy is its continuation by subsequent emperors. The appointments of friendly rulers, the annexation of Cilicia to Commagene and the possible reorganization of Mauretania were not canceled, and Claudius put into practice the invasion of Britain prepared by Caligula.

Assassination of Caligula:

In addition to the failed conspiracy of Gaetulik and Lepidus, conspiracies were drawn up against Caligula by Macron and Gemellus, Sextus Papinius and Anicius Cerial and Betilienus Bassus and Betilienus Capito, but they were also exposed. The opposition to Caligula was also made by the philosophers Julius Kahn and Julius Graetsin. It became absolutely clear to Caligula that the opposition of the Senate was principled, and he made no further attempts to reconcile with it. After the conspiracy was discovered, they say, he struck his sword in front of the Senate and exclaimed: “I will come, I will come, and he will come with me.” Because of all this, Caligula’s freedman Protogenes began to carry next to him two books called “Sword” and “Dagger”, where the executions were listed. Despite this, Cassius Chaerea, Annius Vinician and senators Publius Nonius Asprenatus and Lucius Norbanus Balbus resorted to a new attempt. The date of the assassination was set for the Palatine Games, January 24, 41. The conspirators were most afraid of one of Caligula’s bodyguards – a strong and brutal German, and also of the fact that during the games Caligula could go to Alexandria. However, Guy appeared at the ceremonies and in the morning entered a crowded theater where Catullus’ plays were being performed. Since Caligula had the custom of going to the bathhouse and second breakfast in the middle of the day, the conspirators planned to attack him in one of the narrow underground passages. However, Guy decided to stay that day. Vinician decided to warn Chaerea that the moment had passed, but Guy held him by the edge of his toga, asking in a friendly tone where he was going, and Vinician sat down. Asprenatus, unable to bear it, began to advise him to leave the theater. When Guy and his retinue finally began to leave, Caligula’s uncle, Claudius, Marcus Vinicius and Valery Asiaticus got ready. Caligula was walking with his friend Paul Arruntius and suddenly decided to take a shortcut to the baths. On the way, Guy stopped to talk with the youth, and during this time the conspirators managed to move. Chaerea asked him the traditional vulgar password with which Guy had teased him, and heard the usual sarcastic answer, which was a conditioned signal (according to another version, Guy said “Jupiter”, to which Chaerea threw “accipe ratum” – “get yours”). Guy received a slight blow between the neck and shoulders and tried to escape, but one of the conspirators, Sabin, struck him with a second blow. The conspirators surrounded Guy, and Chaerea shouted to Sabin the formula traditionally used during sacrifice – “do this” (lat. hoc age), after which Sabin struck another blow to the chest. After one of the daggers hit the jaw, Caligula received a series of blows. According to Suetonius, Caligula’s last words were “I am still alive,” but the conspirators, finishing off the emperor, dealt him about thirty blows, encouraging each other with a cry: “Strike again!” Along with Caligula, his fourth wife Caesonia and his only eleven-month-old daughter Julia Drusilla (named after the emperor’s deceased sister) were killed. Agrippa later carried Gaius’ body to the Lamian Gardens, an imperial property on the Esquiline outside Rome, where the corpse was cremated and the ashes were placed in a temporary grave. It was said that the ghost of Caligula haunted the Lamian Gardens for some time until the body was properly buried. In 2011, Italian police said illegal archaeologists had discovered and looted Caligula’s tomb near Lake Nemi.