BIOGRAPHY:

The biography of Charles I the Great amazingly combines wars of conquest and educational reforms, cruelty towards enemies and reverent love for family and friends. Not every ruler in world history was destined to become a hero of a folk epic and receive the honorary title of Great.

Childhood and youth:

The future emperor was not born into a royal family, which would be logical to imagine. His father was the court dignitary Majordomo Pepin the Short, heir to the ancient Carolingian family, who also acted as majordomos at the Frankish court. Karl’s mother Bertrada, the daughter of the influential Count of Lansky Calibert, turned out to be a match for her ambitious and power-hungry husband. She was actively involved in politics and was obsessed with the idea of unification with neighboring powers.

By that time, the power of the ruling Merovingian dynasty had weakened so much that state affairs were managed by the king’s closest associate, the mayor, and the monarch signed and nodded his head at meetings with foreign ambassadors. In 751, Pepin the Short, with the support of the Pope, finally dethroned the last of the Merovingians and proclaimed himself the first Carolingian ruler. His sons Karl and Carloman were also anointed to the kingdom. The monarch, deprived of power, was sent to a monastery, and the Pope, in gratitude, received lands in the center of Italy. Charles grew up as a strong, active and inquisitive boy, showed remarkable abilities in learning and was distinguished by a calm, flexible character. These qualities made the boy his father’s favorite; from the age of twelve, Pepin took him with him on military campaigns and taught him to jointly conduct government affairs.

In 768, Pepin unexpectedly died of dropsy and the kingdom, according to his will, was divided between his sons. Charles received the northern and western lands, and Carloman the central and southeastern parts. Immediately after this, relations between the brothers deteriorated, and ill-wishers tried to quarrel between them. Things were heading towards war, and only the efforts of the mother prevented an internecine conflict from flaring up.

The situation resolved itself: in 771, Carloman suddenly died. Charles sent his widow and children away to Italy and immediately annexed his brother’s lands to his own, declaring himself the sole king of the Franks. Thus he became the most powerful ruler in Europe. He owned most of the modern territory of France, Belgium, almost all of Germany with Austria included in it, and part of the Netherlands. Therefore, Charles immediately began to strengthen his possessions, while simultaneously annexing neighboring territories.

Military campaigns:

He began his reign with a war with the Saxons, which lasted a total of 33 years. The Saxons were pagans and constantly harassed the Franks with their cruel and treacherous raids. In 772, Charles and his army captured their fortress of Eresburg and destroyed the main shrine – the idol of Irminsul. After this, a truce was concluded for a while, and the king moved to Italy, which then belonged to the Lombards and was led by his father-in-law Desiderius. The Lombards constantly encroached on the papal lands and threatened to seize Rome, so the pope asked Charles for help.

The conquering king also had his own interest in this war, therefore, divorcing Desiderius’ daughter and sending her to her father, he entered the war. The path of his army lay through the Alps, and, realizing that the Lombards had fortified the pass, Charles unexpectedly approached them from the rear. This sowed panic among Desiderius’s troops, and he was forced to retreat to the Lombard capital of Pavia, hoping to fortify the city and sit out the siege. Six months later, the capital fell, and Desiderius surrendered to the mercy of the winner. He was captured and tonsured a monk, and Charles declared himself king of the captured lands and introduced Frankish rule to them. In Rome, the winner was greeted with the greatest honors, and Pope Adrian I organized a ceremonial reception for him. In 776, the pope once again turned to Charles for military help. The son of Desiderius entered into an agreement with the Byzantines and intended to take the throne. Soon the uprising was suppressed and the rebels were punished.

After the Italian campaign, Charles again took up Saxony. While the king was fighting in Italy, the Saxons recaptured Eresburg. Therefore, Charles decided to erect a powerful defensive line on the border with Saxony and built the Karlsburg fortress, which was designed to protect the Frankish lands from enemy raids. At the same time, there was an active conversion of the local population to the Christian faith, sometimes accompanied by fierce resistance. In 777, the governor of Zaragoza came to Charles with a request for help. The king had long been planning to expand his southern borders, and, taking advantage of the opportunity, went to the Pyrenees. This trip was not very successful. In the Ronselvan Gorge, the Basques organized an ambush for his soldiers and carried out a bloody massacre. Karl’s nephew Roland died in this battle. This episode formed the basis of the legendary epic “The Song of Roland.” However, Charles still managed to win back a piece of territory at the foot of the Pyrenees Mountains, which he called the Spanish March. Upon Charles’s return, unpleasant news awaited him: the treacherous Saxons forgot all their promises and again started a war. Therefore, the king prepared his new campaign in Saxony with special care. He managed to pacify his enemies for a while and put people loyal to him at the head of the administrative districts, but after a while a rebellion broke out again in Saxony.

At the same time, he baptized his four-year-old son Pepin and declared him king of the Lombards.

In 788, Charles annexed Bavaria, forcing his cousin Thassilon to renounce the dukedom, accusing him of conspiracy and placing him in a monastery.

Returning to Saxony, the king set about suppressing the uprising organized by the leader of the pagan resistance, Widukind. He devoted three years to this, mercilessly destroying the rebellious and their homes. Soon the rebels asked for mercy and surrendered. Widukind himself came to the king and, having repented, accepted Christianity. This was the turning point in the long and bloody Saxon War.

One of Charles’s outstanding achievements in the military field is considered to be the conquest of the Avars, or, as they were also called, the Huns. This war became the second longest and bloodiest after the Saxon one and lasted fourteen years. The Avars tribe, which terrorized the inhabitants of eastern Europe for several centuries, was destroyed, and their lands were annexed to the Frankish state, receiving the name Eastern March. All the wealth looted by the Avars during their existence went to the winners.

In 799, the protracted war in Saxony was successfully completed. Charles and his sons finally defeated the Saxons, settling the conquered territories with the Franks, and scattered the captured Saxons throughout the territory of the Frankish state.

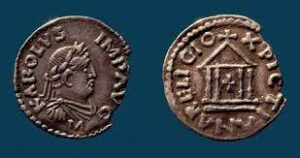

Building an Empire:

In 799, as a result of a conspiracy, Pope Leo III was overthrown. He turned to Charles for protection and was soon returned to Rome. The local nobility had no choice but to come to terms with this state of affairs. During the Christmas mass, the pope, in gratitude, proclaimed Charles emperor. Despite the dissatisfaction of the Byzantine rulers, they had to recognize the new title of the ruler of the Franks. To catch up with them, Charles attempts to marry the Byzantine Empress Irene, but in the same year she lost power as a result of a palace coup. The formation of the empire was the most important event for Western Europe, uniting royal power and the church, strengthening the influence of the Frankish state.

Charles I, being an intelligent, religious and educated man, could not help but understand the enormous role of the church in the development of the state. Therefore, he rewarded devoted clergymen in every possible way, generously giving them monetary and land rewards. In response, they diligently introduced the conquered peoples to the Christian faith, ensuring careful observance of humility and law-abiding.

The era of Charlemagne is called the “Carolingian Renaissance”. He gathered the most educated people of that time at court and contributed to the opening of schools, not only for the nobility, but also for the middle class. Under him, ancient chronicles began to be collected, which were copied and systematized in special scriptoria at monasteries. Libraries were created, and a reform of writing and the education system was carried out. Under him, abandoned lands were reclaimed, new cities, bridges and roads were built. The empire created by Charlemagne was inherited by his son Louis after his death and collapsed in 843. The reason for the collapse was the insufficiently authoritarian power of his heirs, who did not possess such outstanding qualities inherent in their great predecessor.

Rule Of The Empire:

Mark acquired a consular position at the age of 19, which was a great honor. In 161, when the young man was re-elected to the post of consul for the third time, the ruler Antony Pius died. It fell to his two sons, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Ceionius, to rule the Roman Empire. For eight years the brothers ruled the state jointly, but Lucius soon died. Power completely passed into the hands of Mark.

From the first days of his reign, the young emperor demonstrated immense respect for the Senate and ancient traditions. Aurelius paid great attention to the judicial system, preferring instead of dubious reforms to strengthen the original Roman legal foundations. The emperor immediately gained a reputation as a wise, sensible ruler, and his penchant for deep reasoning became the philosophy of those years.

During the reign of Marcus Aurelius, a lot was done for the poor. Programs have emerged to support large families and help people in need.

The emperor himself was a peace-loving man, but he also had to take part in several battles. After the death of Anthony Pius, neighboring Parthia boldly violated the borders with Rome, defeating the imperial troops in two battles. It was necessary to make peace with the aggressors, and on conditions that were very unfavorable for the empire. Before this situation had time to subside, the northern borders of Rome were attacked by Germanic tribes.

Aurelius’s army suffered one defeat after another, which forced the ruler to change his attitude towards financing the army. He increased the military budget and created additional legions that were supposed to defend the state’s borders. To achieve this, the conscription had to be expanded: even famous gladiator fighters and strong slaves were recruited into the army.

From the east, Rome was constantly attacked by the Sarmatians, in battles with which Mark personally led the army. But when the Romans managed to launch a successful offensive, a plague epidemic began to rage among the soldiers.

Philosophical Works:

From his youth, Aurelius devoted a lot of time to the study of philosophy. His inspiration and adviser was the consul Quintus Junius Rusticus, an ancient Roman Stoic philosopher.

Despite the busy government schedule, the ruler found the opportunity to write books. In total, over the years of his life, Mark created twelve works in Greek, many quotes from which became aphorisms. The author’s works received the general title “To Myself,” or, in other translations, “Alone with myself,” “Reflections about myself.”

The emperor himself could not have imagined that two thousand years later his descendants would study his books with trepidation. He kept records in the form of personal diaries, in which he reflected on duty, life and death. He analyzed situations from his own life when the need arose to suppress anger in himself in response to human meanness.

Like no one else, Marcus Aurelius felt responsible for the future of the Roman people. From within, society consumed itself with immorality and ignorance, and from without, it was destroyed by regular attacks by barbarians. The situation in the state was extremely difficult, but the ruler tried not to succumb to anger, hatred and despondency.

The position of humility and suppression of internal anger was not invented by Aurelius. The ancient Greek philosopher Epictetus, who by the will of fate became a Roman slave, helped him form his own picture of the world. The great Roman and the wise Greek taught people not to be upset by the imperfections of the world and people, but to accept them as they are.

In those years, paganism was preached in Rome, and the Christian religion was persecuted in every possible way. Nevertheless, the emperor’s writings clearly show a tendency towards a Christian perception of the world. The philosopher was close to the theory of monotheism – the belief in the existence of a single principle that governs everything on Earth.

Aurelius’s monotheism was once again confirmed by the German humanist Xylander, who did a great deal of work studying the book “Discourses on Oneself.” The scientist drew a number of analogies from the works of the Roman philosopher with the holy book of Christians – the New Testament.

Personal life:

Charlemagne had six wives, three concubines and eighteen children. His first wife was the daughter of the Lombard king Desiderius. He sent her to his father before the start of the first Italian campaign and soon married a girl of noble birth, Gildegarde, who bore him three sons (Pippin, Charles and Louis) and three daughters.

From childhood, the king taught his sons hunting, horse riding and sword handling, and also welcomed their studies in grammar and exact sciences. He adored his daughters so much that he always tried to keep them with him and never married them off. And Karl doted on his sons, so the untimely death of Pepin and Karl became a real tragedy for him.

Death:

By the end of his life, Karl turned into a sick, decrepit old man. Feeling his imminent death, he crowned Louis the Pious and publicly declared him his heir.

Soon after this, he caught a cold while hunting and died in the seventy-second year of his life, in the forty-seventh year of his reign. His body was solemnly laid to rest in the main cathedral of the city of Aachen.