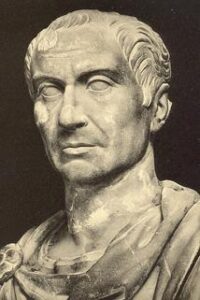

Gaius Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (100-44 BC) – Roman politician and commander. In 68 he was elected quaestor, in 65 aedile. By organizing magnificent spectacles and grain distributions, Caesar gained popularity among the people. In 62 he became praetor. Commanding troops in Farther Spain, Caesar in 61. made several campaigns against the Callaiki and Lusitanians, during which he made a fortune and gained military glory. His star rose in 59, when he was elected consul. Having concluded an agreement with Marcus Crassus and Gnaeus Pompey, Caesar shared power over Rome with them. Both Gaul and Illyria were assigned to him as provinces.

In 58-51 Caesar waged numerous wars that ended with the subjugation of the free Gallic tribes inhabiting the territory between the shores of the Atlantic Ocean and the Rhine to Rome. In 58, he defeated the Helvetii and the German leader Ariovistus; in 57

Caesar launched a campaign against the Belgae, and in 56 against the Veneti and Aquitani. In 54 he crossed to Britain and conquered a number of tribes. Meanwhile, the Gauls rose up in the liberation struggle, led by the leader Vercingetorix. It took Caesar two years to cope with the Gauls. In the summer of 52 he surrounded the rebels in Alesia. All attempts of the Gauls to break through the blockade ring were unsuccessful; in October 52, Vercingetorix surrendered. Most of the Gallic tribes after this hastened to lay down their arms, and in 51 Caesar finally pacified Gaul. Meanwhile, conflicts in the Roman state led to strained relations between Caesar and the Senate. Caesar refused to surrender his province to the successor appointed by the Senate. On January 10, 49, he crossed the border along the Rubicon River and marched an army towards Rome. There was no resistance to him. Caesar easily captured Rome and Italy. His political opponents, united around Gnaeus Pompey, fled to Epirus. In March 49, Caesar went to Spain to neutralize the seven legions stationed there under the command of Pompey’s legate Lucius Afranius and Marcus Petreius. On August 2 he won a victory at Ilerda and returned to Rome in October.

In January 48, Caesar landed in Epirus. In July, having failed at Dyrrhachium, he retreated to Thessaly and there on August 9 he completely defeated Pompey at the Battle of Pharsalus. Pursuing the fleeing Pompey, Caesar arrived in Egypt at the end of September 48, where he learned of the death of Pompey by order of the Egyptian king Ptolemy XIII. This allowed him to intervene in Egyptian affairs. In the so-called War of Alexandria, Caesar took the side of Queen Cleopatra. With only a small force at his disposal, Caesar won the Alexandrian War and established Cleopatra on the Egyptian throne.

In the summer of 47, Caesar marched to Asia Minor against the Bosporan king Pharnaces II, the son of Mithridates VI Eupator, and on August 2, 47, defeated him. In October, Caesar landed in Africa, where the remnants of the Pompeians consolidated. At the Battle of Thapsus on April 6, 46, he destroyed their troops and defeated the Pompeians’ ally, the Numidian king Juba I. In May, with a triple triumph for the Gallic, Alexandrian and Numidian Wars, he entered Rome and was declared dictator.

In December 46, Pompey’s son Magna Gnaeus took possession of Spain. Caesar arrived in Spain and finally destroyed the armed opposition at the Battle of Munda. Upon returning to Rome, he began to carry out reforms to strengthen the state, shaken by continuous wars. Caesar’s plans also included two major campaigns against the Parthians and Dacians. However, they never took place: on March 15, 44, Caesar was killed by conspirators from his inner circle.

Suetonius on Julius Caesar:

“They say he was tall, fair-skinned, well-built, his face was slightly full, his eyes were black and lively. He was in excellent health: only towards the end of his life did he begin to experience sudden fainting spells and night terrors, and twice during classes he had attacks of epilepsy. He looked after his body too carefully, and not only cut and shaved, but also plucked his hair, and many reproached him for this. His disgraceful baldness was unbearable to him, as it often brought ridicule from his ill-wishers. Therefore, he usually combed his thinning hair from the crown of his head to his forehead; therefore, with the greatest pleasure he accepted and took advantage of the right to constantly wear a laurel wreath.”

Book materials used: Tikhanovich Yu.N., Kozlenko A.V. 350 great. Brief biography of the rulers and generals of antiquity. The Ancient East; Ancient Greece; Ancient Rome. Minsk, 2005.

“We are all slaves of Caesar, and Caesar is a slave of circumstances”

Caesar Gaius Julius (c. 100-44 BC). His activities began during the crisis of the Roman slave republic, civil wars, slave uprisings (the most powerful – under the leadership of Spartacus). Even before the birth of Caesar, after the collapse of the ephemeral empire of Alexander the Great, Rome began to flourish.

In the political struggle between patricians and plebeians, supporters of democracy won, and the power of the People’s Assembly was established. The rights of all citizens were expanded and ensured; under the supreme ownership of the community, there was both collective and private land ownership. Great importance was attached to religious rituals and the cult of ancestors, which further strengthened society and encouraged patriotism. This was very important for creating a strong army, which was forced by constant armed clashes with neighboring tribes and the Gauls invading from the north.

The rise of Rome was favored by its geographical position in the center of the Italian Peninsula on a navigable river near the salt mines. Victories over Carthage in the First and Second Punic Wars (264-241 and 218-201 BC) allowed Rome to spread its influence to Sicily, Spain, and North Africa. Constantly strengthening their army, the Romans switched to a policy of conquest in the East – in Macedonia and Greece.

The successes of the Romans were determined not only by the military valor of citizens and the talents of commanders, but also by the development of spiritual and material culture – based on the great achievements of the Greeks. In particular, the Roman playwright Titus Maccius Plautus continued the traditions of Greek domestic comedy. He ridiculed fortunetellers, seekers of easy money (“We rush after the unfaithful, but we lose the faithful”) and politicians who are good as long as they strive for the goal.

But as soon as they come to her, there are no people worse than them, There are no liars like them!

The plays of Terence, who imitated the Greek comedian Menander, were popular for many decades. After the death of the playwright, Julius Caesar dedicated his epigram to him:

Half-Menander, you are also considered a great poet – And rightly so: you love to converse in pure speech. If it were possible to add comic power to your soft creatures, so that you could equal the Greeks in honor and so that in this too you would be considered no lower than the latter!

The poet Lucillius (who, by the way, fought in Spain) ridiculed the growing rich Roman society, where an immoderate desire for luxury, extortion and embezzlement began to strengthen. Here is a fragment from his satire:

“Now from morning to night, whether on holiday or on weekdays, Whole days and people, just like an important senator

They wander around the forum together and don’t go anywhere.

Everyone indulges in one concern, only art:

Speak carefully and fight each other with cunning,

To argue in flattery, to play a good role for a person,

Build ambushes as if they were all enemies to each other.”

An extraordinary personality was Marcus Terentius Varro (116-27 BC) – the conqueror of pirates, for which he was awarded the “Naval Crown”, as a commander fought in Spain against Caesar, was defeated, but was forgiven, organized a large public library in Rome, became a writer and encyclopedist. The famous politician, orator, writer and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) said about him: “We were strangers in our hometown… Your books seemed to bring us home, told us who we are and where we live.”

Even in Caesar’s youth, the Roman Republic almost became a monarchy. The commander Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138-78 BC), after a series of brilliant victories in Asia Minor and Greece, when he was removed from command, led his army to Rome, defeated the army of his rival Gaius Marius and in 83 BC .e. became a dictator, although after 4 years he voluntarily resigned. Civil strife continued in the country. Two parties were still at enmity: representatives of the patricians – the optimates and supporters of democracy – the popular. But the result of the victory of one or the other was the establishment of a dictatorship (for example, from the first – Sulla, from the second – Maria) and brutal repressions of the vanquished.

All this must be remembered in order to understand the situation in Roman society that was favorable to the establishment of Caesar’s dictatorship. In addition to decisiveness, it is very important in a political struggle to be able to take advantage of the current situation. Caesar mastered this skill to the fullest. In 70 BC. The popular Pompeii and the optimate Crassus became consuls, and the latter, interested in supporting the plebs, went over to the camp of Sulla’s opponents. Returning from exile, Gaius Julius Caesar, Marius’s nephew, made a speech about his merits and restored his trophies, removed by Sulla, to the Forum. Caesar came from a noble family, received an excellent education, mastered the art of oratory and quickly became a prominent politician. He gained popularity among the people by staging magnificent shows. In 63 BC. was elected high priest (pontiff). Then, having become quite rich, he ruled the province of Spain.

Becoming consul in 59 BC, he formed the first triumvirate together with Pompey and Crassus; successfully conducted a military campaign

Pania in Gaul (modern France, Belgium), as well as in Britain. After the collapse of the triumvirate, Pompeii attempted to deprive

Caesar’s power. Caesar was faced with a question: should he cross the Rubicon River with his army, dividing Gaul with Italy, and thereby start a civil war, or agree to resignation?

Caesar crossed the Rubicon, defeated Pompey’s army, invaded Egypt and established the rule of his beloved queen Cleopatra there. In August 47 BC. With a swift blow he defeated the army of the Bosporan king Pharnaces, later describing this event briefly: “I came, I saw, I conquered.” Then he won the battle of Thapsus in Africa against Sextus Pompey and Marcus Porcius Cato. A little later, having finally dealt with his enemies, he was awarded grandiose triumphs in Rome. He was declared dictator for life, “father of the fatherland.” Since then, the name Caesar began to mean “Kaiser”, “tsar” (in Russian we usually say “tsar” instead of the Latin “rex”). Julius Caesar was killed at a Senate meeting by conspirators led by Brutus and Cassius. He left a legacy not only as a brilliant commander and an intelligent statesman, but also as the author of “Notes on the Gallic War” and “Notes on the Civil War,” written in a hammered Latin style.

Caesar became famous first of all as a brilliant commander, who more than once defeated a numerically superior enemy (keep in mind that he got a well-armed, trained, disciplined army). As a statesman, he was distinguished by his prudence, caring for the good of his Motherland. For this reason, he respected Marcus Tullius Cicero, an outstanding politician, orator, writer, and philosopher, although he was his opponent, supporting Pompey. Cicero was even forgiven for the following statement: “We are all slaves of Caesar, and Caesar is a slave of circumstances.” There was a considerable amount of truth in this. After all, Caesar was granted lifelong power as a tribune, an indefinite dictatorship, he was proclaimed emperor and “father of the fatherland.”

Despite the fact that enormous power was concentrated in his hands, Caesar was unable to resolve serious social contradictions in Roman society. Moreover, opponents and envious people intensively undermined his authority, calling him a tyrant and a strangler of freedom. The fact that this was demagoguery, that under the guise of a republican system it was intended to establish the power of the oligarchs, is evidenced by the behavior of the Romans after the assassination of Caesar. When the conspirators stabbed him with daggers at a Senate meeting, the senators fled, their panic spreading to the people. When the murderers, shaking daggers covered in the blood of the tyrant, came out to proclaim the triumph of freedom, the square and streets were empty. Fearing persecution, the conspirators fled to the Capitol. The speech at the Forum of Marcus Brutus was met with silence. Caesar was not condemned as an “enemy of the state”; at the suggestion of Cicero, he was considered dead, and the killers were amnestied.

During Caesar’s funeral, his supporter, the consul Mark Antony, gave a speech praising his virtues and read his will, according to which the poor received generous gifts. The guardian genius Caesar was recognized as divine. A year later, when the second triumvirate, including Antony, came to power, many of Caesar’s enemies, including Cicero, were executed. The army of the conspirators Marcus Brutus and Gaius Cassius was defeated and they died. When the second triumvirate collapsed, Caesar’s great-nephew and heir, Gaius Octavius, won. He defeated Antony’s army, conquered Egypt and became the sole ruler of a huge power. Citizens, tired of strife, political intrigue and civil wars, proclaimed it in 19 BC. High Priest and Father of the Fatherland, bestowing divine honors. Under him, the Roman Empire reached the pinnacle of power, prosperity and cultural development.

Balandin R.K. One Hundred Great Geniuses / R.K. Balandin. – M.: Veche, 2012.

The unity of Caesar. 45 year:

Caesar did not hide his intention to destroy the old order. He seized the treasury in Rome; when one tribune tried to block his way into the temple on the Capitol, where the treasury lay, Caesar threatened him with death, although, according to the old law, the tribune was considered inviolable.

The war between Caesar and his opponents lasted for four years. First, the Republicans under Pompey were defeated at Pharsalus in northern Greece; Pompey himself fled to Egypt to King Ptolemy, but was killed before he could set foot on the shore. Then the Pompeians and the Republicans, among the latter Cato, gathered in Africa; they were again defeated by Caesar, and Cato, considering the cause of the republic lost, pierced himself with a sword. The opponents of Caesar gathered in Spain for the last time. But Caesar had the upper hand everywhere. However, the more effort required in the fight, the more promises he made to his soldiers. Almost every campaign began with a large uprising of soldiers; they refused to serve, summoned the emperor to their meeting and presented him with their demands for rewards in money and land.

Caesar in his triumph showed himself better than Sulla; he did not take revenge on his enemies with opals and even tried to attract many of them, for example. Cicero, to your side. But independent people did not want to humiliate themselves before him: they stood for the old republic. For the nobles, the republic meant that none of them should rise above the others. Among them were strong characters: people like Cato said that the greatest treasures of man are simplicity of life and a calm spirit; If you don’t have the strength to fight against what you consider unjust, a person’s duty is to take his own life. Very many nobles, however, went over to Caesar; they became, as it were, his courtiers and accepted positions according to his appointment instead of waiting for the people’s choice.

Returning to Rome after all the victories, Caesar rewarded his soldiers: each of them received about 2 1/2 thousand rubles in our money, the officers three times more. Then, like Sulla, Caesar was recognized as a dictator without a term. He could declare war and make peace, appoint to all positions, issue orders, dispose of provinces, that is, everything that the Senate and the people had previously decided passed into his hands. As a sign of greatness, Caesar began to constantly appear in a triumphal cloak and wreath. He was recognized as a demigod and a temple was built in his honor. Caesar deliberately humiliated the Senate; he placed undeveloped Gallic officers there and only asked the Senate for its opinion when he liked. He again gave huge exciting games to the population of Rome, and every citizen received a large monetary gift from him. In Italy they were silent for now, but everyone expected with fear that Caesar would take away the land for his soldiers from the peasants and landowners.

Caesar wanted even more – the establishment of royal power. He was preparing a campaign across the Euphrates, against the Parthians, dangerous neighbors of the new Roman possessions, and wanted to connect the proclamation of himself as king with the war*. Then a conspiracy was formed among the nobles to kill him. They were led by the former supporters of Pompey, Brutus and Cassius. The conspirators surrounded Caesar in a Senate meeting and stabbed him with daggers (in 44 BC). But they failed to restore the previous order in Rome.

There were many Caesar’s veterans in the city who were expecting land allocation and in the death of their leader they saw the collapse of all their hopes and calculations. Because of their irritation, the Republicans who killed Caesar fled to the east. Antony, the dictator’s closest assistant, tried to win Caesar’s soldiers over to his side. But 18-year-old Octavian, adopted by Caesar as his nephew, had more success. Old Cicero believed Octavian’s promises to defend the republic against Antony. The soldiers, however, did not want a war between Caesar’s two heirs; they forced Antony and Octavian to make peace and go together to Rome to take revenge on the enemies of the deceased dictator. Everything that happened during the time of Sulla was repeated: two emperors drew up disgraced lists and were among the first to cut off Cicero’s head. They robbed rich people in Rome, took booty from the cities of Italy, and with these funds waged a war with Brutus and Cassius, who fortified themselves in Macedonia.

Caesar’s heirs gained the upper hand, and Cassius and Brutus pierced themselves with swords, like Cato. Their names became household names to refer to the last Republicans. In turn, the name of Caesar (in Greek pronunciation – Caesar) became a household name for later rulers; it was a title they accepted. Caesar’s heirs declared him a god; at the site where his ashes were burned, an altar was erected, which was recognized, along with the temples of the gods, as a refuge for criminals and fugitive slaves. New priests were assigned to serve the new god. Throughout Italy, lands were taken from their owners to be distributed to Caesar’s veterans and the soldiers of the new rulers.

The Republic could not stay in Rome. Any new military leader would do the same as Sulla and Caesar. The whole point was just which of the military leaders would be able to remain above the others.

Notes

* Rumors about Caesar’s intention to proclaim himself king were spread by his opponents in Rome. They remembered the predictions that only a king could defeat the Parthians. In addition, Mark Antony tried to place the royal Diadem on Caesar, which caused indignation among the Romans and seemed to confirm the rumor.

Quoted from: Vipper R.Yu. Ancient world history. M.: Republic, 1993.

Political Activities:

Caesar Gaius Julius (100 or 44 BC), Roman dictator in 49, 48-46, 45, from 44 – for life. Commander. He began his political activity as a supporter of the republican group, holding the positions of military tribune in 73, aedile in 65, praetor in 62. Seeking a consulate, in 60 he entered into an alliance with C. Pompey and Crassus (1st triumvirate). Consul in 59, then governor of Gaul; in 58-51 he subjugated all of Trans-Alpine Gaul to Rome. At 49, relying on the army, he began the struggle for autocracy. Having defeated Pompey and his supporters in 49-45 (Crassus died in 53), he found himself at the head of the state. Having concentrated in his hands a number of the most important republican positions (dictator, consul, etc.), he actually became a monarch. Killed as a result of a Republican conspiracy. Author of “Notes on the Gallic War” and “Notes on the Civil Wars”; carried out a calendar reform (Julian calendar).

Caesar Gaius Julius Caesar (July 13, 100 – March 15, 44 BC), Roman politician and commander. The last years of the Roman Republic are associated with the reign of Caesar, who established a regime of sole power. The name of Caesar was turned into the title of the Roman emperors; Subsequently, the Russian words “tsar”, “Caesar”, and the German “Kaiser” came from it.

Youth:

He came from a noble patrician family: his father served as praetor and then proconsul of Asia, his mother belonged to the noble plebeian family of the Aurelians. Young Caesar’s family connections determined his position in the political world: his father’s sister, Julia, was married to Gaius Marius, the de facto sole ruler of Rome, and Caesar’s first wife, Cornelia, was the daughter of Cinna, Marius’s successor. In 84, young Caesar was elected priest of Jupiter. The establishment of the dictatorship of Sulla in 82 and the persecution of Marius’s supporters affected Caesar’s position: he was removed from the post of priest and a divorce from Cornelia was demanded. Caesar refused, which resulted in the confiscation of his wife’s property and the deprivation of his father’s inheritance. Sulla, however, pardoned the young man, although he was suspicious of him, believing that “there are many Maries in the boy.”

Beginning of military and government activities:

Having left Rome for Asia, Caesar was in military service, lived in Bithynia, Cilicia, and took part in the capture of Mytilene. He returned to Rome after Sulla’s death and spoke at trials. For the sake of improving his oratory, he went to Fr. Rhodes to the famous rhetorician Apollonius Molon. Returning from Rhodes, he was captured by pirates, paid a ransom, but then took brutal revenge by capturing sea robbers and putting them to death. In Rome, Caesar received the positions of priest-pontiff and military tribune, and from 68 – quaestor, married Pompeia, a relative of Gnaeus Pompey – his future ally and then enemy. Having taken the post of aedile in 66, he was engaged in the improvement of the city, organizing magnificent festivals and grain distributions; all this contributed to his popularity. Having become a senator, he participates in political intrigues in order to support Pompey, who was busy at that time with the war in the East and returned in triumph in 61.

Consulate ’59:

In 60, on the eve of the consular elections, a secret political alliance was concluded – a triumvirate – between Pompey, Caesar and the winner of Spartacus, Crassus. Caesar was elected consul for the year 59 jointly with Bibulus. Having carried out agrarian laws, Caesar acquired a large number of followers who received land. Strengthening the triumvirate, he married his daughter to Pompey.

Gallic War:

Having become proconsul of Gaul at the end of his consular powers, Caesar conquered new territories for Rome here. In the Gallic war, Caesar’s exceptional diplomatic and strategic skill and his ability to exploit contradictions among the Gallic leaders were revealed. Having defeated the Germans in a fierce battle on the territory of modern Alsace, Caesar not only repelled their invasion, but then, for the first time in Roman history, he undertook a campaign across the Rhine, crossing his troops over a specially built bridge. Caesar also made a campaign to Britain, where he won several victories and crossed the Thames; however, realizing the fragility of his position, he soon left the island.

In 56, during a meeting of the triumvirs in Luca with Caesar, who had arrived for this purpose from Gaul, a new agreement was concluded on mutual political support. In 54, Caesar urgently returned to Gaul in connection with the uprising that had begun there. Despite desperate resistance and superior numbers, the Gauls were again conquered, many cities were captured and destroyed; by 50 Caesar had restored the territories subject to Rome.

Coin of Julius Caesar depicting captured Gauls and trophies. I century BC.

Caesar the commander:

As a commander, Caesar was distinguished by decisiveness and at the same time caution. He was hardy; on a campaign he always walked ahead of the army – with his head uncovered in the heat, in the cold, and in the rain. Caesar knew how to set up soldiers with a short and well-constructed speech, he personally knew his centurions and the best soldiers and enjoyed extraordinary popularity and authority among them.

Fight with the Senate:

After the death of Crassus in 53, the triumvirate disintegrated. Pompey, in his rivalry with Caesar, led the supporters of traditional Senate republican rule. The Senate, fearing Caesar, refused to extend his powers in Gaul. Realizing his popularity among the troops and in Rome itself, Caesar decides to seize power by force. On January 12, 49, he gathered the soldiers of the 13th Legion, gave a speech to them and made the famous crossing of the river. Rubicon, thus crossing the border of Italy (legend attributes to him the words “the die is cast”, uttered before the crossing and marking the beginning of the civil war).

Civil War:

In the very first days, Caesar occupied several cities without encountering resistance. Panic began in Rome. Confused Pompey, the consuls and the Senate left the capital. Having entered Rome, Caesar convened the rest of the Senate and offered cooperation in joint government. Caesar quickly and successfully carried out a campaign against Pompey in the territory of his province – Spain. Returning to Rome, Caesar was proclaimed dictator. Pompey, teaming up with Metellus Scipio, hastily gathered a huge army, but Caesar inflicted a crushing defeat on him in the famous battle of Pharsalus; Pompey himself fled to the Asian provinces and was killed in Egypt. Pursuing Pompey, Caesar went to Egypt, to Alexandria, where he was presented with the head of his murdered rival. Caesar refused the terrible gift, and, according to biographers, mourned his death.

While in Egypt, Caesar intervened in political intrigues on the side of Queen Cleopatra; Alexandria was subdued. Meanwhile, the Pompeians, of whom Cato and Scipio took the leading roles, were gathering new forces based in North Africa. After a campaign in Syria and Cilicia (it was from here that he wrote in his report “he came, he saw, he conquered”), he returned to Rome and then defeated the supporters of Pompey at the battle of Thapsus (46) in North Africa. The cities of North Africa expressed their submission, Numibia was annexed to the Roman possessions, turned into the province of New Africa.

Caesar the Dictator:

Upon returning to Rome, Caesar celebrates a magnificent triumph, arranges grandiose shows, games and treats for the people, and rewards the soldiers. He is proclaimed dictator for a 10-year term, and soon receives the titles of “emperor” and “father of the fatherland.” Caesar carries out laws on Roman citizenship, on government in cities, on the reduction of grain distributions in Rome, as well as a law against luxury. He reforms the calendar, which bears his name.

After the last victory over the Pompeians at Munda (in Spain, 45), Caesar began to be given immoderate honors. His statues were erected in temples and among images of kings. He wore red royal boots, red royal vestments, had the right to sit on a gilded chair, and had a large honorary guard. The month of July was named after him, and a list of his honors was written in gold letters on silver columns. Caesar autocratically appointed and removed officials from power.

Conspiracy and assassination of Caesar:

Discontent was brewing in society, especially in republican circles, and there were rumors about Caesar’s desire for royal power. His relationship with Cleopatra, who lived in Rome at that time, also made an unfavorable impression. A plot arose to assassinate the dictator. Among the conspirators were his closest associates Cassius and the young Junius Brutus, who, it was claimed, was even the illegitimate son of Caesar. On March 15, 44 – on the Ides of March – at a meeting of the Senate, the conspirators, in front of the frightened senators, attacked Caesar with daggers. According to legend, seeing young Brutus among the murderers, Caesar exclaimed: “And you, my child” (or: “And you, Brutus”), stopped resisting and fell right at the foot of the statue of his enemy Pompey.

Caesar also went down in history as the largest Roman writer – his “Notes on the Gallic War” and “Notes on the Civil War” are rightfully considered an example of Latin prose.

Image of Julius Caesar and Octavian Augustus on a Gallic coin. Around 36 BC

Caesar’s policy:

After the Battle of Munda, Caesar became the sole ruler of the state. He received an indefinite dictatorship, lifelong tribunician power and a “prefecture of morals,” that is, censorship power. Caesar, to a greater extent than any of his predecessors, violated Roman republican traditions by concentrating in his hands the most important magistracies, which made his power unlimited. In addition, he received a number of honorary privileges and titles, among other things—the right to add the title “emperor” to his own name, which emphasized his lifelong connection with the army, the title of “father of the fatherland,” which was supposed to make his personality sacred in the eyes of citizens , the right to constantly wear the clothes of a triumphant, which likened him to Jupiter, which, like his title of great pontiff, gave his power a religious connotation.

In Caesar’s policy it is difficult to trace a clear, consistently pursued political line. “Caesar does not know where he is leading us,” wrote Cicero, “we are Caesar’s slaves, and Caesar is a slave of circumstances.” But these “circumstances” favored Caesar’s implementation of his main goal – the transformation of Rome into a monarchy. According to Suetonius, Caesar argued: “The Republic is nothing more than an empty word without substance or shine. Sulla was a baby in politics, since he voluntarily resigned from his dictatorship.”

The entire previous experience of the struggle to establish a military dictatorship suggested Caesar a certain course of action: the concentration of power based on military force, a more rational use of the wealth of the provinces, the creation of a counterbalance to the Senate oligarchy in the form of a wide bloc of slave owners from various parts of the Roman Empire.

Acting in this direction, Caesar established the collection of direct taxes directly by the state, retaining taxation only for indirect taxes. He issued a new strict law against the abuses of governors and their assistants. For the first time, the widespread colonization of the provinces, projected by Gaius Gracchus, was carried out: 80 thousand veterans, freedmen and the poorest citizens were settled in provincial colonies, which became a reliable stronghold of Roman power. Caesar attracted the top provincials with the generous distribution of Roman and Latin citizenship, which he bestowed on both his individual supporters and residents of Sicily, Spain, and Narbonese Gaul. In the provincial and Italian colonies and municipalities, he tried to ensure a dominant position for local slave owners and his soldiers, who received various privileges. These persons were members of the city councils, which enjoyed some independence from the governors in managing the economic life of the city. Some cities in Asia and Greece received autonomy.

Strengthening his power, Caesar replenished the Senate with his supporters from military commanders and natives of Italian cities and even provinces, bringing the number of senators to 900. He also increased the number of magistrates, which he gave to his proteges. Since the real force on which Caesar relied was the army, he not only generously rewarded the soldiers with money on the occasion of magnificently celebrated triumphs, but also systematically allocated them land. This was all the more necessary for him because even during the Civil War, fermentation began among the soldiers, who demanded dismissal from the army and into open revolts.

However, Caesar’s policy of creating a strong military monarchy was not consistent. He deprived the Senate of real political power, but, by abandoning proscriptions, did not undermine the economic power of the Senate, which consisted mainly of the largest landowners. Almost all prominent Pompeians were forgiven by him, and many of them received high appointments. Formally recognizing his power and subservient to the all-powerful dictator, they did not, however, reconcile themselves with the limitation of their role in politics and with Caesar’s monarchical aspirations. The campaign Caesar was preparing against the Parthians, which, if successful, was supposed to further strengthen his power, made these circles fear that sooner or later Caesar would achieve the proclamation of himself as king.

At the same time, a split began among the Caesarians. Caesar, who for many years acted as the leader of the popularists and with their help paved his way to power, began to infringe on the interests of the plebs. The hopes of the plebeians for the accumulation of all debts were not justified. Caesar carried out only a series of partial measures, as a result of which the debts were reduced by 1/4. In Rome, uprisings of the plebs broke out twice (in 48 and 47), which were brutally suppressed by Anthony, to whom Caesar entrusted the administration of Italy. Upon his return to Italy, Caesar dissolved the colleges of the plebs restored under Clodius. He reduced the number of citizens receiving free bread to 120 thousand. The provision of land to the soldiers was slower than they had wished. Finally, the favors that Caesar showered on the forgiven optimates did not please all those who thought that he would put an end to the Senate oligarchy once and for all. Thus, trying to unite various classes, groups and parties, but not satisfying those layers that ensured his victory, Caesar found himself deprived of social supports. A conspiracy was formed against him, in which both representatives of the old nobility and some Caesarians took part. The conspiracy was led by the optimates Cassius and Brutus, who went over to Caesar’s side during the war. On March 15, 44, Caesar was killed by conspirators at a Senate meeting.

Quoted from: World History. Volume II. M., 1956, p. 386-387.

Literature:

Plutarch. Comparative biographies. Julius Caesar. M., 1964. T. 3.

Utchenko S. L. Cicero and his time. M., 1972.

Utchenko S. L. Julius Caesar. M., 1984.

Appian. Roman wars. St. Petersburg, 1994.

Gelzer M. Caesar, der Politiker und Staatsmann, 1960.

Oppermann H. Julius Caesar in Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten. 1968.