BIOGRAPHY:

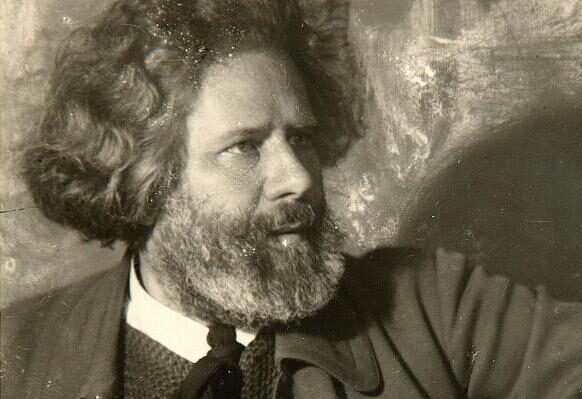

The poet and artist Maximilian Voloshin, expelled from the university, surprised his contemporaries with the versatility of his interests. A creator who knew how to encapsulate the passions raging within within the framework of the poetic genre, in addition to painting and poetry, he wrote critical articles, was engaged in translations, and was also fond of astronomical and meteorological observations.

From the beginning of 1917, his bright life, full of stormy events and various meetings, was concentrated in Russia. At the literary evenings held by the writer in the house he personally built in Koktebel, Korney Chukovsky’s son Nikolai, Osip Mandelstam, Mikhail Bulgakov, and even Marina Tsvetaeva were repeatedly present.

Childhood and youth:

Maximilian Kiriyenko-Voloshin was born on May 28, 1877 in Kyiv, in the family of a collegiate adviser, lawyer Alexander Kiriyenko-Vloshin, a descendant of Zaporozhye Cossacks, and a German woman, Elena Glaser. The boy’s maternal grandfather, Ottobald Glaser, was an engineer colonel. The mother of the future poet had a strong and strong-willed character; she left her husband soon after the birth of Maximilian. Max’s father died in 1881, when he was only four years old, so the boy grew up with his mother without fatherly education. However, it was not needed; the mother herself tried to cultivate fighting qualities of character in her son, but she did not succeed. Marina Tsvetaeva once noted that Max was growing up friendly and peaceful, “without claws.”

At the age of sixteen, Maximilian and his mother moved to Crimea and settled in Koktebel. Elena still did not lose hope of raising him to be a fighter, so she persuaded the neighboring boys to provoke Maximilian into a fight. The mother liked that the teenager was interested in the occult; she did not scold him for spending two years in each class of the gymnasium. According to one of the teachers, Max was a complete idiot, and it was simply impossible to teach him anything. Only six months passed, this teacher died, and at his funeral it was Maximilian who read aloud his extraordinary poems.

In 1897, Voloshin entered Moscow University at the Faculty of Law. He did not miss a single lecture, but the poetically minded student was of little interest in his studies. He was engaged in his self-development outside the walls of the university. The young man never received a university diploma; he was expelled in 1899 for participating in riots. After this, Maximilian no longer tried to continue his studies, he studied independently.

Literature:

Voloshin’s first book, “Poems,” was published in 1910. In the works included in the collection, the author’s desire to understand the fate of the world and the history of mankind as a whole was clearly visible. In 1916, the writer published a collection of anti-war poems “Anno mundi ardentis” (“In the year of the burning world”). In the same year he settled firmly in his beloved Koktebel, to which he later dedicated a couple of sonnets.

In 1918 and 1919, two of his new books of poetry were published – “Iverni” and “Deaf and Mute Demons”. The hand of the writer is invariably felt in every line. Voloshin’s poems dedicated to the nature of Eastern Crimea are especially colorful.

Since 1903, Voloshin has published his reports in the magazine “Scales” and the newspaper “Rus”. Subsequently, he writes articles about painting and poetry for the magazines “Golden Fleece”, “Apollo”, the newspapers “Russian Art Chronicle” and “Morning of Russia”. The total volume of works, which to this day have not lost their value, amounts to more than one volume.

Since 1903, Voloshin has published his reports in the magazine “Scales” and the newspaper “Rus”. Subsequently, he writes articles about painting and poetry for the magazines “Golden Fleece”, “Apollo”, the newspapers “Russian Art Chronicle” and “Morning of Russia”. The total volume of works, which to this day have not lost their value, amounts to more than one volume.

In 1913, in connection with the sensational attempt on Ilya Efimovich Repin’s painting “Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan,” Voloshin spoke out against naturalism in art by publishing a brochure “About Repin.” And although after this the editors of most magazines closed their doors to him, considering the work an attack against the artist revered by the public, in 1914 a book of Maximilian’s articles “Faces of Creativity” was published.

Painting:

Voloshin took up painting in order to judge fine art professionally. In the summer of 1913, he mastered the technique of tempera, and the following year he painted his first sketches in watercolor (“Spain. By the Sea”, “Paris. Place de la Concorde at night”). Poor quality watercolor paper taught Voloshin to work immediately in the right tone, without corrections or blots.

Each new work of Maximilian carried a particle of wisdom and love. While creating his paintings, the artist thought about the relationship between the four elements (earth, water, air and fire) and the deep meaning of the cosmos. Each landscape painted by Maximilian retained its density and texture and remained translucent even on canvas (“Landscape with a lake and mountains”, “Pink Twilight”, “Hills parched by the heat”, “Moon whirlwind”, “Lead light”).

Maximilian was inspired by the classic works of Japanese painters, as well as the paintings of his friend, the Feodosian artist Konstantin Bogaevsky, whose illustrations adorned Voloshin’s first collection of poems in 1910. Along with Ivan Aivazovsky, Emmanuel Magdesyan and Lev Lagorio, Voloshin is today considered a representative of the Cimmerian school of painting.

Reaction to revolutionary upheavals:

Voloshin led an active creative and social life and was a prominent critic. Participated in the construction of a cultural anthroposophical center in Switzerland. He sharply opposed any military actions and refused to participate in them. He painted a lot and organized personal exhibitions.

He perceived the revolutionary events of 1917 very negatively. During this period he lived in Koktebel. During the civil war, he did not take either side, opposing violence in general. In his house he sheltered those who needed protection: red from white, white from red.

In the 1920s, Voloshin was actively involved in social activities in Crimea, organized artistic and scientific studios, and was involved in the protection of cultural and artistic monuments. Conducted cultural and educational work and taught. In 1927 he married Maria Zabolotskaya. It was she who, after Voloshin’s death, managed to preserve his legacy and house in Koktebel.

Voloshin wrote many critical, socio-political and analytical articles, poems, essays, and translations. Today his work can be found in books:

“Silver Age. Poems”;

“And we are like gods, we are like children…”;

“Wanderer to the Universes.”

Maximilian Voloshin died on August 11, 1932 in Koktebel and was buried on Mount Kuchuk-Enyshar. As the poet predicted, his poems were forgotten for a long time. Until 1961, they were prohibited from publication in the USSR, but were actively distributed in the form of samizdat.

PERSONAL LIFE:

Since childhood, Maximilian was a plump, short boy, whose only advantage was the gorgeous hair on his head. Looking at the appearance of the young man, women did not see in him the masculinity and strength inherent in real men. The eccentric writer was not perceived as a man, but rather as a friend with whom you could go to the bathhouse without experiencing any discomfort.

However, this female opinion had absolutely no influence on the personal life of the writer; his amorous piggy bank was replenished with enviable regularity. The first time Maximilian married the artist Margarita Sabashnikova, the affair with whom began in the most suitable place for this – the city of Paris. They attended lectures together at the Sorbonne, during which Voloshin drew attention to a pretty girl, whose appearance reminded him of Queen Taiakh.

On the day they met, Maximilian invited the girl to the museum and took her to the statue of the Egyptian ruler. He wrote to friends about this discovery of his, that he did not fully understand how this could be. It seemed to the artist that the statue came to life and reincarnated as his chosen one, Margarita. Friends joked about this and earnestly asked him not to marry the alabaster statue.

The lovers got married in 1906 and settled in St. Petersburg, next door to the famous poet Vyacheslav Ivanov. A Symbolist meeting was held in his apartment once a week. Often the newlyweds, Maximilian and Margarita, were also present at these gatherings. While Voloshin enthusiastically recited his poems and participated in various disputes and discussions, Margarita quietly talked with the owner of the apartment, Ivanov. She complained that her idea of the life of a real artist did not coincide with reality, that she lacked passion and drama, and that the fashion for friendly married couples had long passed.

Gradually, feelings began to arise between Vyacheslav Ivanov and Margarita. Voloshin at this time fell in love with the playwright Elizaveta Dmitrieva. In 1909, Maximilian and Elizabeth came up with the image of a mysterious Catholic beauty for her and gave her the name Cherubina de Gabriac. Under this pseudonym, Dmitrieva published her works on the pages of Apollo magazine.

This hoax was exposed literally three months later. In November of the same year, 1909, Nikolai Gumilyov gave a negative assessment of the poetess, which Maximilian heard. But it was Gumilyov who brought Voloshin and Dmitrieva together. Maximilian really didn’t like Gumilyov’s statement addressed to Elizabeth, and he gave the poet a resounding slap in the face.

After this, Voloshin and Gumilev had no choice but to meet in a duel. Maximilian tried to defend the honor of the beautiful lame girl. The duel took place on the Black River, fortunately, none of the duelists were injured. After this, Voloshin’s legal wife announced to him that she was filing for divorce. Later it became known that Vyacheslav Ivanov’s wife invited her to live together, and Margarita agreed.

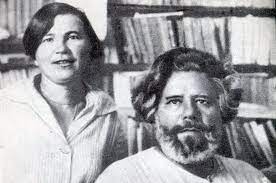

In 1922, famine came to Crimea. Voloshin’s mother, Elena Ottobaldovna, was getting worse day by day. Concerned about the state of her health, Maximilian persuaded paramedic Maria Zabolotskaya from a neighboring village to move to their village. But this didn’t help much; the poet’s mother died. But there were changes in the artist’s personal life – in 1927 he married Maria, who supported him all this time.

In 1922, famine came to Crimea. Voloshin’s mother, Elena Ottobaldovna, was getting worse day by day. Concerned about the state of her health, Maximilian persuaded paramedic Maria Zabolotskaya from a neighboring village to move to their village. But this didn’t help much; the poet’s mother died. But there were changes in the artist’s personal life – in 1927 he married Maria, who supported him all this time.

There were no children in any of Voloshin’s marriages. The artist’s union with Maria was no exception. Their family life proceeded amicably and harmoniously, Maria was always there, in days of sadness and in joyful days, until Voloshin’s death. After his funeral, the widow preserved the entire way of their Koktebel life, constantly receiving artists and poets who visited Koktebel in the house of her late husband.

Death:

The last years of the poet’s life were full of work – Maximilian wrote and painted a lot in watercolors. In July 1932, the asthma that had long troubled the publicist was complicated by influenza and pneumonia. Voloshin died after a stroke on August 11, 1932. His grave is located on Mount Kuchuk-Yanyshar, located a couple of kilometers from Koktebel.

After the death of the eminent writer, sculptor Sergei Merkurov, who created the death masks of Leo Tolstoy, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Mikhail Bulgakov and Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, took a cast from the face of the deceased Voloshin. The writer’s wife, Maria Zabolotskaya, managed to preserve the creative legacy of her beloved husband. Thanks to her efforts, in August 1984, Maximilian’s house located in Crimea received the status of a museum.

Bibliography:

1899 – “Venice”

1900 – “Acropolis”

1904 – “I walked through the night. And the flames of pale death…”

1905 – “Taiah”

1906 – “Angel of Vengeance”

1911 – “To Edward Wittig”

1915 – “To Paris”

1915 – “Spring”

1917 – “The Capture of the Tuileries”

1917 – “Holy Rus’”

1919 – “Writing about the kings of Moscow”

1919 – “Kitezh”

1922 – “Sword”

1922 – “Steam”

1924 – “Anchutka”