BIOGRAPHY:

Thutmose III Menkheperra (or Minkheperra) – the sixth pharaoh of the XVIII dynasty of ancient Egyptian pharaohs (1490, actually 1468-1436 BC; according to other sources, 1479-1425 BC, 1503-1447 BC or 1525 -1471 BC). Modern Egyptologists consider him the first known conqueror and military genius in world history, calling him “Napoleon of the Ancient World” (this is indirectly confirmed by the relatively low height of the pharaoh – about 162 cm, which, however, is less than the height of the French emperor).

The name Thutmosis (Thutmosis or Thutmoses) is an ancient Greek pronunciation of the Egyptian name Djehutimesu – “the god Thoth is born” (sometimes translated as “born of Thoth”). As a throne, Thutmose III used the name Menkheperra (Minkheperra), which is transmitted in the Amarna Letters as Manahbiria, or Manahpirra.

Family:

Thutmose III was the son of Pharaoh Thutmose II (reigned 1494–1490 BC), married to his half-sister Hatshepsut, and the low-born concubine (or minor wife) Isis. Thus, Thutmose III was the stepson and nephew of Queen Hatshepsut (throne name Maatkara), who alone ruled in 1490/1489-1468 BC. e. Hatshepsut was the fourth (and only surviving) daughter of Pharaoh Thutmose I and Queen Ahmose, making her the direct heir to the throne according to the tradition of the 18th Dynasty.

After the early death of his father, the young Thutmose III was proclaimed the new pharaoh, and Hatshepsut as his regent. After becoming pharaoh, the young pharaoh continued to be raised at the temple of Amun in Thebes in a spirit of reverence for religion and probably received a quality education. Even as a child, the new pharaoh married Hatshepsut’s eldest daughter Nefrura, who did not live to adulthood. Therefore, the main wife of Thutmose III was the second daughter of Hatshepsut, Meritra Hatshepsut (however, some researchers dispute the queen’s motherhood in relation to Meritra).

Thutmose and Hatshepsut:

May 3, 1489 BC e., that is, 18 months after ascending the throne, the young pharaoh, who simultaneously performed the ritual functions of the priest of Amun in the main temple of the god in Thebes, was removed from the throne by the legitimist party, which elevated the heiress of the ancient royal blood, Hatshepsut, to the throne. During the ceremony in the temple of the supreme god Amun, the priests carrying the barge with the statue of the supreme god knelt right next to the queen, which was regarded by the Theban Oracle as a blessing from Amon to the new ruler of Egypt.

Hatshepsut, relying on the support of the favorite and architect Senmut, who was originally a poor provincial official, as well as many representatives of the “intellectual elite”, including the architects Tuti and Ineni, the black general Nehsi, and Hapuseneb, the vizier and high priest of Amon, pursued an active policy to strengthen the internal state of Egypt. Endowed with outstanding political abilities and an extraordinary mind, the female pharaoh restored the monuments destroyed by the Hyksos at Karnak and Luxor and created her own grandiose temple at Der el-Bahri (near Thebes). In addition, recent research has proven that Hatshepsut (who was previously credited with a passive and peaceful foreign policy, which resulted in the weakening of Egypt’s power in the international arena) personally led military campaigns (including the first of two campaigns in Nubia) and controlled southern Syria and Palestine. However, Hatshepsut’s most famous foreign policy action is the equipment in 1482/1481 BC. expedition to Punt (East Africa).

During Hatshepsut’s lifetime, Thutmose III was admitted to command posts in the Egyptian army. He probably led a series of campaigns in Sinai, Nubia and Palestine, in which his talent as a commander first manifested itself. The support of Thutmose III by the army forced the queen to seriously consider the pharaoh who had been removed from government.

After the death of Hatshepsut in early 1468 BC. e. Thutmose, in retaliation for the deprivation of his power, ordered the destruction of all information about Hatshepsut and all her images, but did not cause serious damage to the funeral temple of Hatshepsut in Der el-Bahri – several statues of the queen located in the temple were broken, but the building itself was not damaged. The thirty-meter-tall obelisks of Hatshepsut in Karnak were covered with stone masonry, and her name itself was supposed to be consigned to oblivion – it was knocked out of the cartouches and replaced with the names of Thutmose I, Thutmose II and Thutmose III. The destruction of a name in Ancient Egypt was equated to a curse, so the pharaohs of the early XVIII dynasty erased all inscriptions belonging to the period of the hated Hyksos kings, just as Horemheb, having cursed Akhenaten, by hollowing out the name “Pleasing Aten” from the royal cartouches, sought to destroy information about the existence of his religious reform .

Confusion with the cartouches of Hatshepsut, replaced by the cartouches of her father, husband and stepson, led to the creation of a theory by the German Egyptologist Kurt Zethe that explained the events of the queen’s reign as civil strife between the aging Thutmose I and Thutmose II on the one hand, and Thutmose III and Hatshepsut on the other. The queen’s closest associates were also subjected to repression, including the late Senmut, whose tomb was devastated, and Tuti, who was replaced as chief architect and chief of artisans by Pharaoh’s protege Menkheperraseneb (“Live Menkheperra”), who also took the post of chief of the gold and silver treasury.

However, in parallel with the generally accepted version of the revenge of Thutmose III, there is an alternative point of view on the reason for the persecution of the memory of his predecessor – probably these actions were necessary for the pharaoh only to prove the legitimacy of his rule. This hypothesis is partially confirmed by recent studies conducted by various scientists led by Charles Nims and Peter Dorman. These researchers, having studied the destroyed images and inscriptions, came to the conclusion that the monuments of Hatshepsut’s time could have been damaged after the 42nd year of the reign of Thutmose III, and not in the area of the 22nd, as previously thought, which refutes the well-known theory of the revenge of the conquering pharaoh to his usurper stepmother. Thus, it seems quite possible that Thutmose III, following the advice of those close to him, was forced to eliminate traces of Hatshepsut’s rule due to the very conservative hierarchical political system of Ancient Egypt, which allowed only men to rule the state. Indeed, until the beginning of the reign of the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty, the sovereign rulers of Egypt, in addition to Hatshepsut, were only a few women – Nitokris (Neitikert) at the end of the Old Kingdom, Nefrusebek (Sebeknefrura) at the end of the Middle Kingdom and Tausert at the end of the 19th dynasty. All of them came to power at critical periods in Egyptian history, when the problem of succession to the throne became more complicated, and ruled for only a short time. Therefore, the long and successful reign of Hatshepsut violated tradition and did not fit into the official canon of the development of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Discussing the reasons for the posthumous persecution of the female pharaoh, some Egyptologists even deny them systematicity, putting forward the hypothesis that her cartouches could have been damaged as a result of Akhenaten’s atonistic religious revolution: part of the queen’s royal name, Henemetamon, included the name of Amun, therefore, was subject to ban and destruction. Seti I, who restored the monuments of the 18th dynasty damaged under the “heretic king”, by virtue of tradition, in place of the erased cartouches, could enter the names not of the queen herself, but of her closest relatives.

Thutmose III at the Battle of Megiddo:

Having become the sole ruler, Thutmose immediately began active military activities. In the spring of 1468 BC. e. He set out with an army, estimated at 10,000 – 25,000 soldiers, from the border fortress of Djaru on a campaign against the rebels of ca. 1472 BC e. (the exact date is very difficult to establish, but in 1475 BC the Eastern Mediterranean was still subject to the rule of Hatshepsut) of the rulers of Syria and Palestine (Canaan) led by the king of Kadesh, presumably the heir of the Hyksos, since Egypt considered the pacification of the rebels as the last step in destruction of the Hyksos yoke. For the first time after the restoration of Egyptian independence, the state no longer had to face the scattered resistance of individual princes, as was the case under the predecessors of Thutmose III, including Thutmose I, but with a large coalition, which was also probably supported by military assistance from the Central Asian powers. Only some cities of Southern Palestine remained loyal to the Egyptian authorities, including Sharukhen, where a confrontation broke out between pro-Egyptian and pro-Mitannian forces.

The pharaoh did not follow the advice of his military leaders and chose the shortest, but at the same time the most dangerous, of the three routes to Aruna – through a mountain pass along a narrow gorge, along which the Egyptians moved in a narrow column, led personally by the pharaoh. However, such a decision only misled the enemy, who expected that the Egyptians would move along the Tanaakh road, and only 21 days were spent on the entire journey from Djaru to Megiddo.

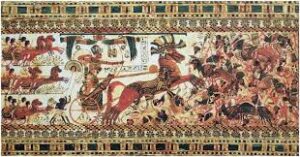

At the southern stronghold of the rebels, Megiddo, located at the crossroads of trade routes, on May 15, 1468 BC. e. the first documented battle in history took place (Megiddo would later be the scene of many battles in subsequent history, right up to Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign, and in the Apocalypse of John the Evangelist it would be assigned the role of the site of the final battle between the forces of good and evil). The day before, May 14, 1468 BC. e. Thutmose chose a tactically correct place for the deployment of his troops: he ordered the troops to be stretched west of Megiddo in order to cut off the enemy’s retreat to the north and ensure the possibility of his own retreat to Zefti in case of failure.

A brilliant commander, Thutmose, personally leading the war chariots stationed in the center, completely defeated the scattered Syrian-Palestinian troops. Although the coalition forces of the Asian cities attacked first, trying to cut off the Egyptian army from the city, they fled to Megiddo at the first onslaught of the Egyptians. Residents of the city pulled the soldiers of the allied armies inside the fortress with the help of tied clothes. However, due to the fact that the Egyptian infantry began to plunder the rich camp of the Syrian-Palestinian troops abandoned near the walls of Megiddo, Thutmose III was unable to immediately take the Megiddo fortress.

The rich booty captured by the Egyptians in an abandoned camp did not make any impression on the pharaoh – he addressed his soldiers with an inspiring speech, in which he proved the vital necessity of taking Megiddo: “If you had then taken the city, then I would have accomplished today (the rich offering) to Ra, because the leaders of each country who rebelled are locked in this city and because the captivity of Megiddo is like the capture of a thousand cities.” The Egyptians’ military equipment was probably not yet equipped for assault, so they began to prepare for a long siege, as a result of which Megiddo was surrounded by an Egyptian siege wall called “Thutmose Besieging the Asiatics”. During the siege, the rulers of Syrian cities arrived with tribute to Thutmose, having escaped encirclement in the key fortress of Palestine.

The resistance of the Syrians and Palestinians defending the famine-stricken Megiddo was broken only after 7 months as a result of the siege. 330 local princes who rebelled against Egyptian power were captured. Thutmose treated them extremely humanely (as was the case at that time), allowing everyone to return home after taking an oath of allegiance from them. True, he emphasized their subordinate position by sending the former rebels home on donkeys. The Egyptians captured rich war booty at Megiddo: 924 chariots, 2,238 horses, 2,000 head of cattle and 22,500 head of small livestock. In addition, the relatives of the rebellious king of Kadesh, who remained in Megiddo, were taken hostage, but Thutmose III did not cause them any harm and even ordered them to be treated with respect.

After the victory at Megiddo, many Palestinian and Syrian fortresses, in particular the three allies of Kadesh – Inoam, Nuges and Herenkeru – surrendered to Thutmose III without resistance. The sons of the rulers of these areas were taken hostage and sent to be raised in Egypt – thus Thutmose III gave rise to a practice that the Egyptian administration used throughout the New Kingdom, since it both neutralized the possibility of anti-Egyptian unrest and ensured the loyalty of local city rulers Eastern Mediterranean, brought up at the Egyptian court, to the power of the pharaoh. Thutmose III took several more enemy fortresses in Southern Lebanon and founded one new one between the mountain ranges of Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon – “Menkheperra Hika-Ha-sut” (“Menkheperra, Expelling the Hyksos”, or “Menkheperra, Binding the Barbarians”). Manetho, quoted by ancient authors, talks about Misphragmuthosis, confusing in his personality the acts of Ahmose I and Menkheperra-Thutmose and, accordingly, the liberation movement against the Hyksos and the final defeat of the remnants of the Hyksos tribal union. In total, 119 cities were taken during the first military campaign. Thus, during his first campaign, Thutmose III subjugated significant territories to Egypt, right up to the south of Phenicia and Damascus in the north.

The story of the first campaign of Thutmose III ends with the image of the triumph of the pharaoh, who returned to Thebes with his army in early October 1468 BC. e. In honor of his grandiose victory, Thutmose III organized three holidays in the capital, lasting 5 days. During these holidays, the pharaoh generously presented gifts to his military leaders and distinguished soldiers, as well as temples. In particular, during the main 11-day holiday dedicated to Amun, Opet, Thutmose III transferred to the temple of Amun three cities captured in Southern Phenicia, as well as vast possessions in Egypt itself, on which prisoners captured in Asia worked (it is noteworthy that Thutmose III did not turn them into slavery in the full sense of the word, but assigned them to the corresponding areas as formally free community members).

Next year – 1467 BC. e. – Thutmose III repeated the campaign in Syria, without a single battle, instilling even greater fear in the Asian states. Assyria, which at that time was a minor Central Asian state, which, due to its temporary decline, paid tribute to Mitanni and Babylon, took the Egyptian conquests in the Eastern Mediterranean as a chance to find a reliable ally, so it sent Thutmose III, who was still on campaign, rich gifts consisting of horses and various precious stones.

Further military campaigns of Thutmose:

In total, Thutmose led 17 military campaigns in Western Asia, during which he subjugated the lands up to the Euphrates, took 367 cities and fortresses and faced the Mitannian kingdom (known to the Egyptians and Western Semites as Naharin, that is, “the region of rivers”), a powerful state in Northern Mesopotamia, ruled by the Hurrian elite. The military activities of Thutmose III in Nubia were limited to a number of punitive expeditions. All military operations were carried out in the spring and summer, when it was possible to ensure the army’s food supply.

The third and fourth campaigns of Thutmose III, although we know practically nothing about them (in fact, no evidence at all has survived about the fourth campaign), were probably intended to strengthen the power of the Egyptian administration in Palestine. To provide rear support during the conquest of Syria, Thutmose III developed a complex plan that included not only the capture of Kadesh, but also the conquest of the Phoenician coast. To this end, Thutmose III created a powerful navy (later improved with the help of the Phoenicians), led by a veteran of Thutmose II’s campaigns, Nibamon. Thutmose III used his new fleet for the first time during the fifth campaign (1461 BC) to land troops in Jahi (Phenicia). The Egyptians celebrated their complete victory: one king was captured, the cities of Tunip and Arad (Arwad) were plundered, and around the city of Arad, famous for its wine, fields were burned and groves were destroyed. The rich coastal cities, in particular Tire, observing the numerous Egyptian troops, immediately agreed to surrender. For its submission, Tire received additional privileges and was turned into a real Egyptian outpost on the Mediterranean Sea.

Most likely, it was to this campaign that folk tradition tied the late (from the 20th Dynasty) legend about the fall of Jaffa. This legend about the Syrian campaign is in many ways consonant with the story of the Trojan Horse, so famous in antiquity, and tells about the capture of Jaffa, in ancient times known as Joppa or Yolpa, by the troops of the Egyptian commander Tuti. The cunning Tuti invited the enemy king and several of his associates supposedly “to negotiations,” where he gave them drink, and put a hundred Egyptian soldiers in empty huge wine vessels. When these vessels were brought into the city, the hidden Egyptians cut off the guards and opened the city gates to their troops. Some researchers see in the legend about Tuti a prototype of the Homeric story about the capture of Troy with the help of the Trojan Horse and the Arabian tale of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

In 1460 BC. e. The pharaoh once again led his troops to put an end to the king of Kadesh, who betrayed the pharaoh for the second time by betraying the concluded treaty. Thutmose ordered the felling of Lebanese cedar to build a siege around Kadesh, and with the help of his general Amenemheb, he took the fortress by storm. Having strengthened his power in Retenna (Syria), the pharaoh, during his next campaign, also landed in the Phoenician city of Simirna, from where he attacked the nearby town of Ulladze, where one of the princes of Tunipa, who led the uprising against Egypt, was captured (April 27, 1459 BC) . Having reached the Euphrates, Thutmose III received the ambassadors of Hatti and Babylon, who presented rich gifts to the pharaoh.

In 1457 BC. e., having pacified Phenicia, the pharaoh set out on his first campaign against the Mitannians. At the beginning of the campaign, Thutmose III landed in the harbor of Simira, took Qatna and won the battle of Senzar. Then the pharaoh, after a stubborn battle on the “heights of Van,” took Halpa (now known to Europeans as Aleppo and to Arabs as Aleppo), the former center of the North Syrian state of Yamhad in Northern Syria. During the campaign, the army was accompanied by boats from Byblos, which were transported using carts drawn by oxen. On the Euphrates this fleet was launched, and the pharaoh easily took several fortified border fortresses. Moving along the Euphrates, the Egyptian army captured Nya, a key Mitanni outpost that opened the way to Northern Mesopotamia. Having defeated the Mitannian king Shaushshatara at Karkemish and crossed the Euphrates, Egyptian troops captured a number of Mesopotamian fortresses. The last city to fall before the attacks of Thutmose III was probably Vashshukani, the capital of Mitanni (this is indirectly indicated by Mitanni sources; the Annals of Thutmose III themselves do not mention the capture of the Mitanni capital). The Mitanni king Shaushshatara capitulated and signed a peace treaty, paying an unprecedented tribute to the victors. While crossing the Euphrates back to Syria, Thutmose III discovered on the western bank of the river the slab of his grandfather Thutmose I – the first pharaoh to reach the “Great Bend of Naharina” (Euphrates) – and installed his own nearby.

After the destruction of the Phoenician coast with the cities of Irkata and Canna, the Egyptians approached Tunip. The city did not put up serious resistance, but the pharaoh came out against Kadesh only in the middle of summer, when his soldiers removed the harvest from the fields near Tunip. Devastating populated areas along the way, Thutmose III led his troops up the Orontes, to the fortified Kadesh. During the final battle, the king of Kadesh resisted to the last, using the most unimaginable tricks. For example, he released a mare onto the battlefield, which caused confusion among the horses harnessed to the Egyptian chariots. However, the pharaoh’s faithful military leader Amenemheb killed the horse (in the autobiography of this nobleman this episode is described very colorfully – a jubilant Amenemheb presents Thutmose with the severed tail of a mare), restoring the front lines of charioteers. Thus, the Egyptians were able to launch a lightning attack, as a result of which the pharaoh’s guards made a hole in the wall of the besieged city and took Kadesh. The fortifications of the city were razed to the ground, and the rebellious ruler of Kadesh, who rebelled against the powerful pharaoh three times, most likely died during the assault.

The pharaoh, who in two decades had subjugated the entire Eastern Mediterranean to his power, enjoyed enormous authority in Babylon, among the Hittites and in Crete, who, out of fear of the military power of Egypt, sent him gifts that were not much different from tribute. The memory of the conquering pharaoh was preserved for a long time among the peoples of Syria-Palestine he conquered: even a century later, loyal Egyptian vassals in the region mentioned “Manakhbiriyah” (Menkheperru-Thutmose III), appealing to Akhenaten with pleas for military assistance.

Domestic policy:

Under Thutmose III, construction work inside Egypt did not stop. Traces of the construction activities of Thutmose III have been preserved in Faiyum (a city with a temple), Kumma, Dendera, Koptos (Kopte), El-Kab, Edfu, Kom Ombo, Elephantine. Construction was carried out with the help of prisoners of war, and the architectural designs were often drawn up by the pharaoh himself, which testifies to certain creative talents of the king. The most ambitious construction project of Thutmose III was the Karnak Temple of Amun-Ra. In fact, it was rebuilt by the chief architect Puemra on the thirtieth anniversary of his reign (1460 BC), when the pharaoh participated in the heb-sed ceremony. In addition to the general changes in the temple, jubilee obelisks were erected, one of which is now destroyed, and the second, containing a mention of Thutmose “crossing the Bend of Naharina,” is located in Istanbul. Under Thutmose III in Heliopolis in 1450 BC. e. Two more large obelisks were erected – the so-called “Cleopatra’s Needles”. At 19 AD e. The obelisks, by order of the Roman emperor Augustus, were moved to Alexandria. One of them fell on its side and was taken to London in 1872, and the other was brought to New York in 1881. Also under Thutmose III, the obelisk at the Temple of Ra in Heliopolis was begun, completed under Thutmose IV.

The right hand of the pharaoh, the chati (equivalent to the vizier in medieval Muslim countries) of Upper Egypt Rekhmir (Rekhmira) effectively ruled Upper Egypt during the military campaigns of Thutmose III, but the pharaoh himself proved himself to be a talented administrator. It is thanks to the images and texts in the Rekhmir tomb that we know the order of government in New Kingdom Egypt. Another faithful associate of Thutmose III was a descendant of the early dynastic rulers of Thinis, Iniotef (or Garsiniotef), who ruled the oases of the Libyan Desert, and was also to some extent an analogue of Napoleon’s Mamluk Rustam, since he prepared the royal apartments. In peacetime, Thutmose III was engaged in the construction of temples, especially dedicated to the supreme god of Thebes, Amon. For the sake of the needs of the temples of Thutmose in 1457 BC. e. again equipped an expedition to Punt, trying not to be inferior to Hatshepsut in its scope. Myrrh, ivory, gold, ebony and cattle were brought from Punt in large quantities.

Thutmose III paid special attention to the complete incorporation of Nubia, led by the “Chief of the Southern Countries” Neha, into Egyptian structures, especially in the last years of his life. Perhaps the pharaoh personally visited Nubia in the 50th year of his reign. Such attention to the southern province of the Egyptian state is explained by the fact that the gold mines of Nubia brought huge profits – more than 40 tons of gold were mined per year, and this figure was surpassed only after 1840. During his reign, Egyptian temples were built throughout Nubia. For example, in Semna, the restoration of the temple of Khnum, built by Senusret III, one of the most powerful rulers of the 12th dynasty, was carried out.

Thutmose III was the first pharaoh whose interests went beyond state activities. Thutmose III’s outlook, although against his will, was formed under the influence of the pharaoh’s stepmother, who patronized the arts in every possible way. This fact explains the broad outlook and interest of Thutmose III in culture, which was uncharacteristic for an ancient Eastern ruler. The inscription in the Karnak Temple reports a list of plant and animal species unknown to the Egyptians, brought into the country from Asia by special personal order of the pharaoh. In addition, as evidenced by the relief in the Karnak Temple, the pharaoh devoted his free time to modeling various products, in particular vessels. He handed over his projects to the chief of artisans of state and temple workshops. It is difficult to imagine any other pharaoh engaged in such an activity. It is interesting that the first glass products that have survived to this day were created in Egypt under Thutmose III, and keep the name of this pharaoh.

We know about the military activities of Thutmose III from the meager remains of the Annals of Thutmose III, preserved in 223 lines inscribed on the walls of the temple of Amun-Ra, built in honor of the pharaoh’s heb-sed ceremony, in Thebes in the form of excerpts from the chronicle. The leather scrolls of the chronicle, unfortunately, perished, but what was preserved on the stone, in combination with other documents that have survived to our time, makes it possible to follow the progress of the almost continuous military campaigns of Thutmose III, which lasted 20 years. However, from the rich description of the military activities of Thutmose III, mainly meticulous descriptions of the trophies obtained survived, and only information about the battle of Megiddo was laid out practically without abbreviations. The author of the Annals of Thutmose III is the military scribe Tanini, who accompanied the pharaoh on all his campaigns. In the preserved tomb of Tanini in Sheikh abd el-Qurna (Sheikh abd el-Qurnakh), the royal chronicler left his autobiography, directly indicating that he accompanied the pharaoh on each of his campaigns and was the author of the chronicle of the military campaigns of Thutmose III. In particular, the scribe states that he “… followed the good god, the king of righteousness. I saw the victories the king won in all countries… I immortalized the victories he won in all countries in writing…”

Tomb:

Thutmose III died on March 11, 1436 BC. e. (on the 30th day of the month of the 54th year of his reign), leaving his son Amenhotep II a huge state, which was the hegemon in the entire Middle East. An inscription in the tomb of the king’s closest associate, Amenemheb, confirms that Thutmose III reigned for 53 years, 10 months and 26 days – the third longest reign of an Egyptian pharaoh (only Pepi II and Ramses II reigned longer – 94 and 67 years, respectively). Amenhotep II (1436–1412 BC), who had been his father’s co-ruler during the last two years of his reign, would lead another punitive campaign into Asia, accompanied by atrocities against the local population, in sharp contrast to his father’s humane treatment of prisoners of war, after which the Egyptian dominion in Syria and Palestine would remain unbroken until the reign of Akhenaten.

The “Napoleon of the Ancient World” was buried in the Valley of the Kings in tomb KV34. The tomb of Thutmose III was discovered in 1898 by an expedition led by French Egyptologist Victor Loret. In the tomb of Thutmose III, Egyptologists first discovered the complete text of Amduat – “The Book of the Underworld,” which James Henry Brasted called “a monstrous work of perverted priestly fantasy.” Amduat, in a unique fantastic manner, tells the story of twelve caves of the underworld, traversed by the Sun-Ra during twelve hours of the night.

The mummy of Thutmose III was discovered back in 1881 in a cache in Der el-Bahri near the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut Djeser Djeseru. Mummies were placed in such caches starting from the end of the 20th Dynasty, when, by order of the High Priest Amon Herihor, most of the mummies of the rulers of the New Kingdom were transferred, the safety of which was in danger due to the increasing robberies of tombs. Next to the mummy of Thutmose III, the bodies of Ahmose I, Amenhotep I, Thutmose I, Thutmose II, Ramesses I, Seti I, Ramesses II and Ramesses IX, as well as a number of rulers of the 21st dynasty – Siamon, Pinedjem I and Pinedjem II were also discovered.

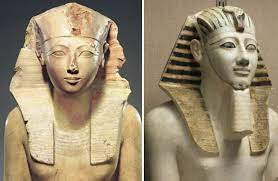

While not possessing an exact portrait likeness, the statues of the pharaoh are still far from the idealized image of the Egyptian pharaoh, quite accurately reflecting individual facial features of Thutmose III, for example, the characteristic “Thutmose nose” and the narrow cheekbones of the conqueror. However, some researchers point out that stylistically many of his statues have the features of his predecessor Hatshepsut, who was depicted as a male pharaoh (almond-shaped eyes, a somewhat aquiline nose and a half-smile on her face), which indicates a single canon for the image of pharaohs of the 18th dynasty. Often, distinguishing a statue of Hatshepsut from that of her successor requires a range of stylistic, iconographic, contextual and technical criteria. There are also many examples of statues depicting a kneeling Thutmose III offering milk, wine, oil or other offerings to the deity. Although the first examples of this style are already found in some of Thutmose’s successors, its spread under Thutmose is believed to indicate changes in the social aspects of Egyptian religion.