BOGRAPHY:

On the chilly morning of November 2, 1872, two police officers walked down Wall Street to arrest a woman. If you believe the yellow newspapers, she is either a prostitute or a thief. But in fact – a broker who decided to run for president of the United States. When the police knocked on the door of her office, a carriage rushed past – the same woman was a passenger. After a short chase, the carriage was stopped and the woman was arrested on charges of sending obscene publications by mail. The detainee behaved calmly and coolly and, as the New York Herald reported, “immediately stated that she was ready to accompany the officers.”

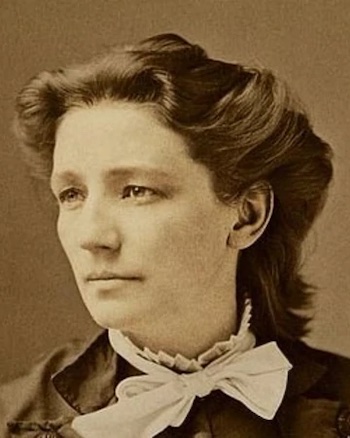

Victoria Woodhull’s life as a whole resembles an adventure novel, rather than the career of a purposeful politician. At the time of his arrest, the US presidential candidate was only 34 years old. She was born on September 24, 1838 in the American outback – in Ohio. She did not receive a systematic education, because after three years of studying at a school at a local Protestant church, her family left the city – her father, Reuben Buckman Claflin, was suspected of deliberately setting fire to his mill in order to fraudulently receive insurance payments. After escaping, Victoria’s family sold homemade medicines, moving from place to place.

In 1853, 15-year-old Victoria Claflin married 28-year-old Dr. Canning Woodhull and took her husband’s surname. The couple had two children. Canning turned out to be an alcoholic, constantly cheated on his wife and, according to her, once dropped his newborn son, which left the boy with a serious head injury. Victoria had to support her children on her own. At first she performed in theaters in San Francisco as an actress, and at the age of 19, together with her younger sister Tennessee Claflin, she began conducting sessions of spiritualism, calling herself a “clairvoyant” capable of healing the sick.

The fashion for spiritualism then coexisted with faith in scientific progress, which, in turn, sometimes took the form of pseudoscientific teachings. Woodhull’s life embodied the contrasts of the era: a “soothsayer” vying for the presidency; a feminist who frightened her allies with her tumultuous personal life; daughter of poor parents who became a successful financier

Wall Street and free love:

In 1865, Victoria divorced her husband and a year later married a second time – to Colonel James Harvey Blood. At that time, divorced women were condemned, but Victoria responded by criticizing double standards: why does society secretly allow men to change their mistresses, while instructing women to remain married despite infidelity and abuse? Woodhull began to support the free love movement. The concept of living with one partner until “death do us part” seemed wrong to her. Like other supporters of the movement, Victoria sought to destigmatize divorce – so that wives would have the opportunity to leave relationships, as they would say today, with abusers.

At the same time, Woodhull and her sister continued to conduct seances. One day they were approached by railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who dreamed of contacting his recently deceased wife. Apparently, the businessman was pleased with Victoria’s work, because he gave some financial advice. The sisters saved almost $700,000 (about $15 million in today’s dollars) and opened the brokerage firm Woodhull, Claflin and Company in 1870. Thus, Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin became the first women in history to run their own financial firm on Wall Street. Journalists called them “charming brokers” and “queens of finance.”

Woodhull was interested in more than just personal enrichment. She decided to use influence and media exposure as a resource. In 1869, she joined the suffragettes, spoke at conventions, and fought for workers’ rights in factories, equal access to education, military service for women, and prison amnesty. Together with her sister, she launched the Woodhull and Claflin Weekly. It was a publication with a provocative position at the time, which supported the concept of free love, demanded women’s suffrage, and was the first to publish an English translation of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto.

Woodhull also opposed abortion bans. While acknowledging that their existence was a “bad state of affairs,” she did not believe that repressive laws could solve the problem. “There is only one effective remedy, and that is the personal freedom of woman,” she wrote in the Woodhull and Claflin Weekly in 1871. According to Victoria, everyone should have the right to refuse sex if a woman is not ready to become a mother: “It’s better not to give birth than to give birth to an unwanted child.”

Mrs Satan:

In 1871, Victoria testified before a U.S. House committee, arguing that American women already had the right to vote because all people born in the United States were full citizens under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. And according to the 15th, no one shall be denied the right to vote on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Woodhull argued that the amendments apply to all citizens of the country – including women. She ended her speech with a warning: “If men continue to exclude women from government, then women will have no choice but to lead the government.”

The committee disagreed with her position, but Woodhull’s performance brought her national attention. On May 9, 1872, the National Woman Suffrage Association held its annual convention and decided to create a new Equal Rights Party, which nominated Victoria for the presidency of the United States in the upcoming election. So she again became a pioneer: before her, no woman had participated in the American presidential race. Woodhull planned to make Frederick Douglass, a former fugitive slave and famous abolitionist, her vice president.

Reflecting on her election campaign, Victoria wrote: “While others argued about the equality of men and women, I proved it by running a successful business. While others were trying to prove that women should be treated socially and politically as second-class creatures, I entered th

e political arena and took advantage of the rights I already possessed.”

In fact, Victoria’s nomination as a candidate for the presidency was more of a symbolic step, and the importance of her action was to create a precedent. The chances of being elected were almost zero, since Woodhull was not yet 35 years old when the election campaign began, and her main electorate – women – could not vote for her (even Victoria herself would not be able to vote for herself). American women received this right to vote only 48 years later.

American society reacted to Victoria Woodhull’s presidential campaign with both ridicule and caution. Journalists gave her the nickname Mrs. Satan. Thousands gathered to listen to Woodhull’s public speeches about the need for equality in all areas for people of all genders and skin colors. However, she lost supporters due to her views on marriage, which were radical by 19th-century standards, and her support for communism. Reputation scandals

Three days before the vote, Victoria was arrested. This was preceded by two scandalous publications published in the Woodhull and Claflin Weekly. The first concerned the famous New York preacher Henry Ward Beecher. He and Woodhull were once ideological allies, as they both supported abolition and universal suffrage, but the preacher later began to criticize Woodhull for her, in modern parlance, polyamorous views. In retaliation, Woodhull published a detailed account of the clergyman’s infidelities with his friend’s wife. At the end of the article, she wrote that Beecher begged her not to publish the material, threatening to commit suicide, but refused to admit everything himself. Another article described an even more heinous scandal – the famous trader and “Wolf of Wall Street” Luther Challis was accused of seducing two underage girls.

Some historians suggest that Woodhull and her sister tried to blackmail the heroes of scandalous stories and their goal was extortion. But the publications could also be motivated by revenge. One way or another, the articles provided a bargaining chip for Woodhull’s enemies. Using intermediaries, Beecher ordered copies of the Weekly by mail, and upon receiving it, wrote a statement to the police in which he accused Woodhull of sending obscene materials by mail. Based on this statement, she was detained.

Victoria Woodhull was quickly released (she convinced her accusers that there was nothing in her publications that could not be found in the plays of Shakespeare or the Bible), but she felt angry and disappointed. Problems grew, opponents spread defamatory rumors about her. In 1876, Victoria divorced her second husband, and a year later, after the death of the railroad magnate Vanderbilt, she and her sister left for England. There she married wealthy banker John Biddulph Martin, joined the ranks of local suffragettes and launched a new magazine called The Humanitarian.

It was a social and political publication that supported another of Woodhull’s presidential campaigns (she tried again for the presidency in 1892). It published articles and columns devoted to revolutionary ideas – elected government, redistribution of land holdings, universal free education for children, the principle of voluntary consent in sex. And the already mentioned eugenics (the study of methods of influencing the hereditary qualities of future generations with the aim of improving them), which then seemed to be a scientific view of childbirth.

Thus, the mother of a child with mental disabilities turned out to be a supporter of the doctrine, which half a century later became the theoretical basis for the crimes of the Nazis. Woodhull’s life was generally full of contradictions: she was a prominent suffragist, but due to the patronage of rich men and sex scandals, she lost the support of her allies. She was a stockbroker but admired the communist ideas of Marx and Engels. She criticized the institution of marriage, but was constantly married. Either way, Woodhull was definitely a woman ahead of her time.

Nursing:

Soon after moving to New York, Victoria and her sister Tenney went to an audience with the richest man in the country, Cornelius Vanderbilt. The oligarch, who was already over seventy, was interested in spiritualism. He was in mourning for his recently deceased wife. Victoria began conducting séances so that the spirits could give Vanderbilt business advice, and Tenney began treating him with magnetism. There were rumors that his younger sister became his mistress, and Vanderbilt even proposed to her, but was refused. They said he called Tennessee “my little sparrow,” and she called him “old goat.” Be that as it may, in August 1869, Vanderbilt entered into a new marriage, marrying his cousin, who bore an unusual, masculine-looking name: Frank Armstrong Crawford. But the richest man in America did not forget his sisters even after his marriage. In a conversation with a correspondent for the New York Daily Herald, Tenney Claflin said that she and her sister have been interested in securities for a couple of years and that, in her opinion, “a woman is also capable of earning her own living.” , like a man.” When asked if Vanderbilt helps their firm, Tenney said she meets with him often but would not say whether he collaborates with them. The official opening of the company took place at 10 a.m. on February 7, 1870. In the first month and a half of work, Victoria and Tenney earned about $700 thousand trading gold, government and municipal bonds, securities of railway, mining and oil companies. In the back of the building in which the office of their company was located, there was a special door through which only women could enter – rich widows, heiresses, actresses who wanted to manage their finances independently, without the help of male relatives.

With the money they earned at the brokerage firm, the sisters founded their newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin`s Weekly, the first issue of which was published on March 14, 1870. This publication is sometimes mistakenly called the first newspaper in history published by women. In fact, the first was the weekly The Revolution, which was started in 1868 by women’s rights activists Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

The main themes of Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly were the fight for women’s suffrage, spiritualism, vegetarianism, socialism and free love. By free love, Victoria Woodhull understood the freedom to marry, divorce and have children without interference from society and the state. The newspaper also expressed the idea of legalizing prostitution. On December 30, 1871, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly published Karl Marx’s “Manifesto of the Communist Party” for the first time in the United States. The publication’s circulation reached 20 thousand copies. The main authors were the sisters themselves, Colonel Blood and the anarchist-individualist theorist Stephen Pearl Andrews, Tenney’s lover.

Speculating on Wall Street and publishing a newspaper, the sisters ceased to be involved in the affairs of the Institute for the Treatment of Magnetism, which quietly ceased to exist.

However, Victoria’s faith in spirits and the afterlife did not weaken. In 1871, she was even elected president of the American Spiritualist Association.

Battles for morality Sisters Victoria and Tenney had their hair cut short and wore skirts so short that their boots were visible from underneath them. But the scandals associated with their family did not end there.

Victoria Canning Woodhull’s first husband came to New York after an attack of delirium tremens and settled in his ex-wife’s house. The public was outraged by such an insult to public morality, newspapers wrote about the “additional husband” and “bigamy.” But Victoria and Colonel Blood thought they were being noble. Canning was an alcoholic, could not provide for himself, and when sober he helped his family as a doctor and looked after the children.

In 1871, Anna Claflin sued Colonel Blood, accusing him of turning his daughters against her, after which she was kicked out of her home and deprived of her livelihood. Anna was supported by her daughter Mary and son-in-law Benjamin Sparr (they were engaged in their favorite family profession – healing with magnetism). Victoria and Tennessee called all the accusations against them a blatant lie. The judge dismissed the claim, telling Colonel Blood that the only charge that could be brought against him was that he wanted to live with his wife and did not want to live with his mother-in-law.

The trial ended in May, and in June Benjamin Sparr was found dead. He allegedly went to visit his disabled sister in Ohio, but the body was found in the New York French’s Hotel, where Sparr registered under a false name. The corpse had no clothes on (or almost none; different newspapers gave different details).

While the public was watching with great interest the personal life of the Claflin family, Victoria Woodhull showed herself in a new capacity. Following business, she took up another male profession – politics.

On January 11, 1871, Woodhull became the first woman to speak before the United States Congress.

In her speech before the House Judiciary Committee, she said that voting is not a privilege granted by the state, but a constitutional right of all citizens of the United States, including women. Most committee members were not convinced by her arguments.

However, it was decided to refer this issue to the level of individual states. Two committee members, William Loughridge and Benjamin Butler, agreed with Woodhull—to the delight of all American suffragists.

That same year, Victoria and her sister Tennie attempted to vote in the municipal elections, but were prevented from doing so. In March 1871, the Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly newspaper reported Victoria’s intention to run for president of the United States if the party convention supported her. This congress took place on May 10, 1872 at the Apollo Theater in New York (in 1913 a new building was built in its place, which inherited the name). The approximately 300 people gathered in the theater called themselves the People’s Party, the Cosmopolitan Party, the Equal Rights Party and the National Radical Reformers, as the New York newspaper The Sun described what was happening.

At the meeting, a presidium was elected, which included six men and three women. It took four hours, during which about two dozen speakers spoke, to develop the political platform of the party, which was to form the basis of the new Constitution of the United States. The document contained, in particular, the following proposals: all important laws should be discussed by the entire population, taxation should be direct and equal, monopolies should be eliminated, wars should be abolished by the decision of international arbitration, the death penalty should be abolished, all unemployed people should get jobs from government, trade between countries should be free, and the world should be ruled by a common government. Those gathered finally decided on the name of their party – the Party of Equal Rights. At eight o’clock in the evening, Victoria Woodhull gave an hour-long speech to the crowd.

Soon after, he came on stage shouting, “Mr. Chairman!” Judge Carter from Kentucky jumped in. He stated: “I am confident that what I have now said will receive the hearty approval of all members of our assembly. I nominate Victoria Woodhull as the Equal Rights Party’s candidate for President of the United States.”

Everyone present stood up, and for five minutes the air was filled with enthusiastic cries. Women waved their handkerchiefs and cried, men roared with delight, and the room was in turmoil.

Victoria Woodhull has agreed to run for president:

After this, a proposal was made to nominate a representative of the oppressed race – the former runaway slave, writer and educator Frederick Douglass – as a candidate for vice president. Controversy arose over this candidacy. A counter-proposal was made – the vice-presidential candidate should be an Indian, the leader of the Lakota Brule tribe Spotted Tail. As a result, the nomination was nevertheless offered to Douglas, who neither agreed nor refused.

Woodhull’s nomination was met with hostility in the press. Thus, the Chicago Tribune wrote that her candidacy was nominated by “a convention of women suffragists, eight-hour workers, free-love advocates, clairvoyants, spiritualists, prohibitionists, sociologists, internationalists, Indians, men with long hair and one thought, women with short hair and one hobby.”

State house and long road instead of the White House:

The presidential election took place on November 5, 1872. And on November 2, a scandal broke out, which began with a sensational publication in the Woodhull & Claflin`s Weekly newspaper.

Congregational Church minister Henry Ward Beecher, brother of the writer Harriet Beecher Stowe, repeatedly accused Victoria Woodhull of radicalism on gender issues and condemned her concept of free love. From 1860 to 1871, his assistant was the poet and publisher Theodore Tilton. In 1870, Tilton’s wife Elizabeth admitted that she had cheated on him with Beecher. Elizabeth Cady Stanton learned about this from Theodore, then other suffragettes, including Victoria Woodhull.

An article published on November 2 said that the famous priest is a hypocrite who does what he himself condemns. On the same day, Victoria Woodhull and Tennie Claflin were arrested for distributing obscene printed matter by mail and taken to Ludlow Street Jail. On November 6, the day after the election, the sisters were indicted. Listening to the judge’s words, Victoria almost cried, and Tenney looked very depressed. On January 9, Colonel Blood was arrested on similar charges. He was placed in the same prison, in cell 13 (his wife was in cell 11).

Harriet Beecher Stowe called Victoria an insolent witch and a vile prisoner:

Woodhull, Claflin and Blood were released on bail, but had to constantly attend court hearings, as new charges were brought against them by various persons – insult, libel, blackmail. In early June 1873, Victoria Woodhull suffered a heart attack. On June 27, all three were found not guilty in the first case – distribution of obscene printed materials. The judge found that the newspapers did not fall within the definition of obscene paper contained in the charges against them. Subsequently, other trials in which Woodhull, Claflin and Blood were defendants ended in not guilty verdicts. In 1875, another trial that lasted six months became the main entertainment for New Yorkers. Theodore Tilton accused Henry Beecher of having an affair with his wife. The trial ended in nothing – the jury could not reach an agreement.

In 1876, Victoria Woodhull divorced Colonel Blood. That same year, the sisters closed the newspaper, and in 1877 Victoria and Tenney went to Great Britain. According to a legend not supported by facts, their trip could have been sponsored by the heirs of Cornelius Vanderbilt, who died on January 4, 1877, fearing that the sisters might enter into a dispute over the inheritance.

Two years after her sister, on October 15, 1885, Tenney also successfully married. The husband of 40-year-old Tennessee was 68-year-old Sir Francis Cook, widowed a year earlier, owner of one of the largest British trading firms – Cook, Son & Co. The King of Portugal granted Cook the title of Viscount of Montserrat, and five months after his marriage to Tennessee Claflin, Queen Victoria of England created the baronetcy of Cook. Sir Francis became the first Baronet Cook, and his wife Lady Cook (in Portugal, Viscountess Montserrat). Tenney’s husband died the same year as her sister’s husband, and she herself lived until 1923.

Two years after her sister, on October 15, 1885, Tenney also successfully married. The husband of 40-year-old Tennessee was 68-year-old Sir Francis Cook, widowed a year earlier, owner of one of the largest British trading firms – Cook, Son & Co. The King of Portugal granted Cook the title of Viscount of Montserrat, and five months after his marriage to Tennessee Claflin, Queen Victoria of England created the baronetcy of Cook. Sir Francis became the first Baronet Cook, and his wife Lady Cook (in Portugal, Viscountess Montserrat). Tenney’s husband died the same year as her sister’s husband, and she herself lived until 1923.

American women received the right to vote in accordance with the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which came into force on August 18, 1920. Women of color other than white were given full equal voting rights when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965.

Colonel Blood was married again after his divorce from Victoria. In 1885, he went to the British colony of the Gold Coast (modern Ghana) in search of gold. He managed to find gold, but he never returned to America, dying on the Gold Coast on his 52nd birthday.

Both Victoria and Tenney had a successful life in Britain:

Woodhull gave lectures in London (she gave the first on December 4, 1877 in the concert hall of St. James’s Hall, the title of the lecture was “The human body is the temple of God”). One of the lectures was attended by John Biddulph Martin, a partner in the family bank Martins Bank. On October 31, 1883, he married Victoria, who from that time began to bear the name Victoria Woodhull Martin. Under this name, she published The Humanitarian magazine from 1892 to 1901. After the death of her husband in 1901, she stopped publishing and retired to a rural estate, where she died in 1927.